Planetary waves, first found on Earth, are discovered on Sun

Waves may influence space weather, offer a source of predictability

Mar 27, 2017 - by Staff

Mar 27, 2017 - by Staff

BOULDER, Colo. — The same kind of large-scale planetary waves that meander through the atmosphere high above Earth's surface may also exist on the Sun, according to a new study led by a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

Just as the large-scale waves that form on Earth, known as Rossby waves, influence local weather patterns, the waves discovered on the Sun may be intimately tied to solar activity, including the formation of sunspots, active regions, and the eruption of solar flares.

"The discovery of magnetized Rossby waves on the Sun offers the tantalizing possibility that we can predict space weather much further in advance," said NCAR scientist Scott McIntosh, lead author of the paper.

The study will be published next week in the journal Nature Astronomy. Co-authors are William Cramer of Yale University, Manuel Pichardo Marcano of Texas Tech University, and Robert Leamon of the University of Maryland, College Park.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), which is NCAR's sponsor, and by NASA.

On Earth, Rossby waves are associated with the path of the jet stream and the formation of low- and high-pressure systems, which in turn influence local weather events.

The waves form in rotating fluids — in the atmosphere and in the oceans. Because the Sun is also rotating, and because it's made largely of plasma that acts, in some ways, like a vast magnetized ocean, the existence of Rossby-like waves should not come as a surprise, said McIntosh, who directs NCAR's High Altitude Observatory.

And yet scientists have lacked the tools to distinguish this wave pattern until recently. Unlike Earth, which is scrutinized at numerous angles by satellites in space, scientists historically have been able to study the Sun from only one viewpoint: as seen from the direction of Earth.

But for a brief period, from 2011 to 2014, scientists had the unprecedented opportunity to see the Sun's entire atmosphere at once. During that time, observations from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), which sits between the Sun and Earth, were supplemented by measurements from NASA's Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO) mission, which included two spacecraft orbiting the Sun. Collectively, the three observatories provided a 360-degree view of the Sun until contact was lost with one of the STEREO spacecraft in 2014. McIntosh and his co-authors mined the data collected during the window of full solar coverage to see if the large-scale wave patterns might emerge.

"By combining the data from all three satellites we can see the entire Sun, and that's important for studies like this because you want the measurements to all be at the same time," said Dean Pesnell, SDO project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "They’re pushing the boundary of how we use solar data to understand the interior of the Sun and where the magnetic field of the Sun comes from."

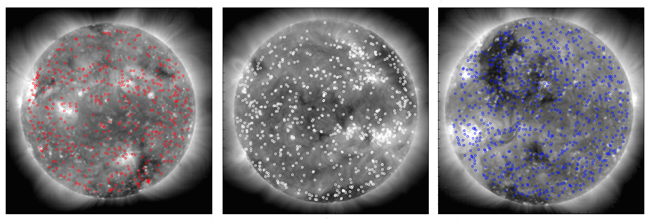

Coronal bright points identified in images of the Sun taken simultaenously from three distinct vantage points in space. From left, images were captured by STEREO-Behind, SDO, and STEREO-Ahead. (Image courtesy Scott McIntosh, NCAR.)

Coronal bright points identified in images of the Sun taken simultaenously from three distinct vantage points in space. From left, images were captured by STEREO-Behind, SDO, and STEREO-Ahead. (Image courtesy Scott McIntosh, NCAR.)

The team used images taken by instruments on SDO and STEREO to identify and track coronal bright points. These small bright features dot the entire face of the Sun and have been used to track motions deeper in the solar atmosphere.

The scientists plotted the combined data on Hovmöller diagrams, a diagnostic tool developed by meteorologists to highlight the role of waves in Earth's atmosphere. What emerged from the analysis were bands of magnetized activity that propagate slowly across the Sun — just like the Rossby waves found on Earth.

The discovery could link a range of solar phenomena that are also related to the Sun's magnetic field, including the formation of sunspots, their lifetimes, and the origin of the Sun’s 11-year solar cycle. "It's possible that it's all tied together, but we needed to have a global perspective to see that," McIntosh said. "We believe that people have been observing the impacts of these Rossby-like waves for decades, but haven't been able to put the whole picture together."

With a new understanding of what the big picture might really look like, scientists could take a step closer to predicting the Sun's behavior.

"The discovery of Rossby-like waves on the Sun could be important for the prediction of solar storms, the main drivers of space weather effects on Earth," said Ilia Roussev, program director in NSF's Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences. "Bad weather in space can hinder or damage satellite operations, and communication and navigation systems, as well as cause power-grid outages leading to tremendous socioeconomic losses. Estimates put the cost of space weather hazards at $10 billion per year."

But to advance our predictive capabilities, scientists must first gain a better understanding of the waves and the patterns that persist on them, which would require once again having a 360-degree view of the Sun.

"To connect the local scale with the global scale, we need to expand our view," McIntosh said. "We need a constellation of spacecraft that circle the Sun and monitor the evolution of its global magnetic field."

Title: The detection of Rossby-like waves on the Sun

Authors: Scott W. McIntosh, William J. Cramer, Manuel Pichardo Marcano, and Robert J. Leamon

Journal: Nature Astronomy, DOI: 10.1038/s41550-017-0086

Writer:

Laura Snider, Senior Science Writer and Public Information Officer