Forecast for big data: Mostly cloudy

UCAR partners with Amazon to provide weather data in the cloud

May 31, 2016 - by Staff

May 31, 2016 - by Staff

May 31, 2016 | The rise of big data has big implications for the advancement of science. It also has big implications for the clogging of bandwidth.

The growing deluge of geoscience data is in danger of maxing out the existing capacity to deliver that information to researchers. In response, scientific institutions are experimenting with storing data in the cloud, where researchers can readily get the relatively small portion of the data they actually need.

Helping blaze the way is Unidata, which partnered with Amazon Web Services last year to make Next Generation Weather Radar (NEXRAD) data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) available in the cloud in near real time. The project is one of the ways Unidata, a community program of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), is exploring what the future of data access may look like.

"One of the roles we play at Unidata is to see where the information technology world is going and monitor the new technologies that can advance science," said Unidata Director Mohan Ramamurthy. "In the last 10 years, we've watched the cloud computing environment mature. It's become robust and reliable enough that it now makes sense for the scientific community to begin to adopt it."

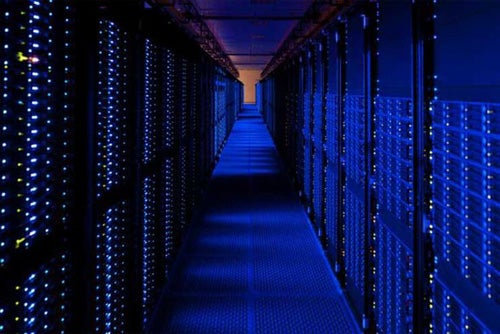

Inside an Amazon Web Services data center. (Photo courtesy Amazon.)

Since 1984, Unidata has been delivering geoscience data in near real time to researchers who want it. Today, Unidata also offers those scientists tools they can use to analyze and visualize the data.

In 2008, Unidata's servers delivered 2.7 terabytes of data a day to 170 institutions. Just five years later, the program was providing 13 terabytes—or the equivalent of about 4.5 million digital photos—a day to 263 institutions.

Today, Unidata is delivering about 33 terabytes of data a day. And the volume is only expected to grow.

For example, NOAA's new weather satellite, GOES-R (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite R-Series), is scheduled to launch in October. When GOES-R is up and running, it alone will produce a whopping 3.5 terabytes of data a day.

"We've been pushing out data for 30-plus years here at Unidata," said Jeff Weber, who is heading up Unidata's collaboration with Amazon. "What we're finding now is that the volume of available data is just getting to be too large," We can't keep putting more and more data into the pipe and pushing it out—there are physical constraints."

The physical constraints are not just on Unidata's side. Many universities and other institutions that rely on Unidata do not have the local bandwidth to handle a huge increase in the incoming stream of data.

To address the problem, Unidata decided a few years ago to begin transitioning its services to the cloud—a network of servers hosted on the Internet that allow you to access and process data from anywhere.

The vision is to create a future where scientists could go to the cloud, access the data they need, and then use cloud-based tools to process and analyze that data. At the end of their projects, scientists would download only their finished products: a map or graph, perhaps, or the results from a statistical analysis.

"With cloud computing, you can bring all your science and the analytic tools you use to the data, rather than the old paradigm of bringing the data to your tools," Ramamurthy said.

These advantages were part of the motivation behind the U.S. Department of Commerce's announcement last spring that NOAA would collaborate with Amazon, Google, IBM, Microsoft, and the Open Commons Consortium with the goal of "unleashing its vast resources of environmental data" using cloud computing.

A NEXRAD data product available to researchers through Unidata. (Image courtesy Unidata.)

Amazon Web Services was one of the first out of the gate on the NOAA Big Data Project, uploading the full archive of NEXRAD data to the cloud last summer. But to figure out how to continue to feed the archive with near real time observations and to help make sense of the data — how people might want to use it and what kinds of tools they would need — Amazon turned to Unidata.

"It made a lot of sense for Unidata to partner with Amazon and vice versa," Ramamurthy said. "They wanted expertise in atmospheric science data. We wanted an opportunity to introduce cloud-based data services to our community and raise awareness about what it can do."

The scientific community is perhaps more hesitant to rely on the cloud than other user groups. Datasets are the lifeblood of many research projects, and knowing that the data are stored locally offers a sense of security for many scientists, Ramamurthy said. Losing access to some data could nullify years of work.

But the truth is that the data are likely more secure in the cloud than on a local hard drive, Ramamurthy said. "Mirroring" by multiple cloud servers means that data are always backed up.

If the Amazon project, and the NOAA Big Data Project in general, are successful in winning scientists over, it could go a long way toward helping Unidata make its own transition to the cloud. Unidata will be studying and learning from the project – including how to make a business model that will work -- with an eye toward its own future.

"We're navigating the waters to find out what works and what doesn't so we can report back to the National Science Foundation," Weber said. "We want to see how this paradigm shift might play out — if it makes sense, if it doesn't, or if it makes sense in a few ways but not others."

Writer/contact

Laura Snider, Senior Science Writer and Public Information Officer