A century of eclipses

Scientists gain fresh insight from old photos in a new NCAR-based digital archive

Jun 10, 2010 - by Staff

Jun 10, 2010 - by Staff

10 June 2010 • Between 1969 and 1971, an NCAR scientist named John Eddy set out to archive an important part of the history of both photography and astronomy. Working with colleagues at NCAR’s High Altitude Observatory (HAO) and other institutions around the world, Eddy collected more than 100 pictures of total solar eclipses taken from the late 1800s into the mid-1900s. Among the photographers were some of the world’s most eminent scientists, including Thomas Edison.

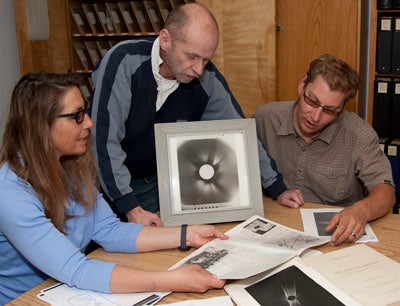

A new online archive of eclipse photos was produced by (left to right) Alice Lecinski, Phil Judge, and Don Kolinski.

Eddy wrote down detailed notes throughout the project, and he and HAO staff made duplicates of each photo. Until recently, this unique and valuable repository remained in the NCAR vaults, but the images are now available for anyone to see and use through an online archive built by HAO’s Phil Judge, Alice Lecinski, and Don Kolinski.

As Judge sorted through the images, he found himself impressed by Eddy’s work. “To devote two years of your life to copying photographic prints and taking meticulous notes—it shows someone who’s a careful, first-rate scientist. This kind of work just isn’t done much anymore,” he says.

Despite the archive’s comprehensiveness, its true value went unrecognized for many years because researchers generally felt that hand-drawn sketches of early eclipses provided more detail than photographs. However, as Judge notes, “different people saw, and drew, different things.” Noting discrepancies among drawings of the same eclipse made by different people, Judge decided to reexamine scans of Eddy’s photographic plates made and catalogued in HAO by Lecinski and Kim Streander in the late 1990s.

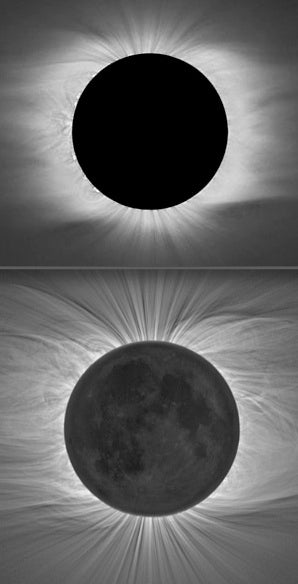

Through modern image processing techniques, NCAR scientists have been able to retrieve valuable data from historical eclipse photos. A composite image of a 1901 eclipse over Sumatra (top) reveals similar structure at higher solar latitudes--evident toward the top and bottom of the photo--as a 2009 digital eclipse image (bottom) from the Marshall Islands. (Imagery courtesy Miloslav Druckmüller)

The scans didn’t yield a great deal of information until recently, says Judge. “When you apply modern digital processing techniques to the photos, you can extract a bit more information,” he says. By using adaptive filters developed by Miloslav Druckmüller (Brno Technical University), the images were converted to a sensitivity that mimics that of the human eye during an eclipse.

The newfound usefulness of the images spurred Judge and Lecinski to ask colleague Don Kolinski for help in putting the scans online. Kolinski converted the 300-plus files to portable image formats and created a simple Web interface (http://mlso.hao.ucar.edu/mlso_eclipse_archive.html), allowing all images to be displayed compactly on a single page.

One recent event that piqued Judge’s interest was the unusually prolonged solar minimum that ended over the last year. “We wanted to know how peculiar the corona of the recent minimum really was,” he says. He and colleagues compared a coronal photo taken by Druckmüller of a 2009 eclipse over the Marshall Islands with images of a 1901 eclipse over Sumatra.

The two images were more similar than anyone expected. Both showed more structure at higher solar latitudes than is typical when an eclipse occurs during a less-extended solar minimum, as was the case in 1954 and 1995. “It appears that this minimum is not that unusual, at least as far as the large-scale magnetic structure of the Sun is concerned,” Judge says.

Judge got an enthusiastic reception when he presented his comparison at a meeting last October devoted to the recent solar minimum. “I got the most interest from any talk I’ve ever given. People were really excited about this.”

Unlike the days of Edison, an eclipse is no longer required to view the solar corona. Special cameras pioneered at NCAR and elsewhere can block the solar disk and render the corona more visible. However, an eclipse still does the job most cleanly, especially when a radial filter blocks the inner corona so that even more of the outer corona is visible in one exposure. NCAR’s Gordon Newkirk refined this technique in the 1960s, and it was used on HAO expeditions from then until the 1990s. The new archive will soon incorporate photos from this period that will complement the earlier shots collected by Eddy.

Judge hopes to give the archive wider exposure through upcoming journal and magazine articles. He’s still struck by the ability to extract useful detail from duplicates of century-old photos: “This is just fascinating stuff to me. Few would have believed you could do this.”

A workshop to honor Eddy’s legacy

In his long career at NCAR, UCAR, and elsewhere, astrogeophysicist John “Jack” Eddy, who died in 2009, worked tirelessly to expand the circle of people interested in solar research. While serving as director of UCAR’s former Office for Interdisciplinary Earth Studies, Eddy held key conferences on past Earth cycles and other discipline-straddling topics. “He wanted to attract students from diverse areas into solar research,” says NCAR’s Phil Judge.

In that spirit, Judge has secured a NASA grant that will bring 20 to 30 undergraduates to a Colorado symposium on 22–24 October designed to stimulate interest in Sun-climate connections. Details on the workshop are at http://www.hao.ucar.edu/EDDY2010.

One of Eddy’s most noted achievements was characterizing the Maunder minimum in sunspot activity, which extended from about 1645 to 1715, and noting its potential connections with the Little Ice Age. The possible link still intrigues people, though the case is far from airtight, says Judge. For one thing, the Little Ice Age lasted more than 200 years, while the Maunder sunspot minimum only straddled about 70 years. “In my mind, it’s not yet a well-grounded area of research,” says Judge. He hopes to see more attention devoted to this and other such problems involving the Sun’s influence on climate.

In a 1976 talk at NCAR, Eddy pondered the existential side of solar research: “Humanity, seeking assurances of immortality, always wanted the Sun to be perfect. When we found it wasn't perfect, we said, well, at least it is constant. And when we suspected it wasn't constant, we comforted ourselves with the thought that, at the very least, it is regular. But it seems to be none of these things.”