Scientists test system to forecast flash floods along Front Range

Jul 22, 2008 - by Staff

Jul 22, 2008 - by Staff

BOULDER—People living near vulnerable creeks and rivers along the Front Range may soon get advance notice of potentially deadly flash floods, thanks to a new forecasting system being tested this summer by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). Known as the NCAR Front Range Flash Flood Prediction System, it combines detailed atmospheric conditions with information about stream flows to predict floods along specific streams and catchments.

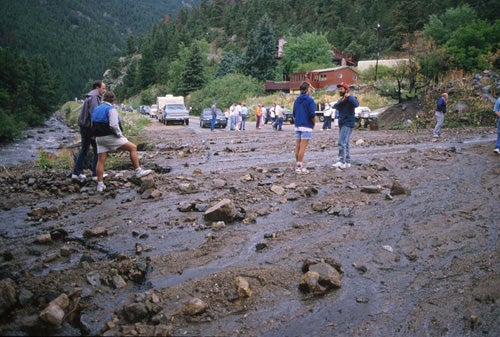

Flood aftermath. [ENLARGE] (©UCAR, photo by Carlye Calvin.) News media terms of use*

Flood aftermath. [ENLARGE] (©UCAR, photo by Carlye Calvin.) News media terms of use*

"The goal is to provide guidance about the likelihood of a flash flood many minutes or even hours before the waters start rising," says NCAR scientist David Gochis, one of the developers of the new forecasting system. "We want to increase the lead time of a forecast, while decreasing the uncertainty about whether a flood will occur."

Funding to create the system was provided by NCAR's sponsor, the National Science Foundation, as well as by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Front Range, because of its steep topography and intense summer storms, is unusually vulnerable to summertime flash floods. The Big Thompson Canyon flood on July 31, 1976, killed 145 people, and deadly floods have also struck elsewhere in the region, including Fort Collins, Buffalo Creek, and Denver.

David Yates. [ENLARGE] (©UCAR, photo by Carlye Calvin.) News media terms of use*

David Yates. [ENLARGE] (©UCAR, photo by Carlye Calvin.) News media terms of use*

Flash floods are difficult to predict because they happen suddenly, often the result of heavy cloudbursts that may stall over a particular watershed. Forecasters can give a few hours' notice that weather conditions might lead to flooding, and radars can detect heavy rain within minutes. But whether a flood hits a specific river or creek also depends on soil, topographic, and hydrologic conditions that are characteristic of particular watersheds. Thus, emergency managers may not know that a flash flood is imminent until the waters begin to rise.

David Gochis. [ENLARGE] (©UCAR, photo by Carlye Calvin.) News media terms of use*

David Gochis. [ENLARGE] (©UCAR, photo by Carlye Calvin.) News media terms of use*

The goal of the NCAR system is to provide officials at least 30 minutes warning of flash flooding in specific watersheds, and possibly as much as an hour or two. It is designed to pinpoint whether a particular stream, such as Clear Creek or Cherry Creek, is likely to overflow, as well as forecast the likelihood of flash floods producing flooding events across a larger region.

NCAR scientists this summer will monitor the system's performance each day, tracking potential flood events from Colorado Springs in the south to Fort Collins in the north. They are working to make forecast products accessible to the National Weather Service and Denver's Urban Drainage and Flood Control District. After this summer's test of the system, researchers will evaluate its performance and make improvements as needed.

"This summer is a proof-of-concept test," Gochis says. "If we can show that our system has some reasonable skill in predicting floods, we think officials may become more interested in using it along with their existing suite of tools."

How it works

The system uses National Weather Service radar observations of current conditions and short-term computerized weather forecasts. The weather forecasts are generated by the NCAR-based Weather Research and Forecasting model (WRF), which produces highly detailed simulations of the local atmosphere.

The system integrates the weather information with data sets about hydrology and terrain. These data sets incorporate information about land surface conditions, such as terrain slope, soil composition, and surface vegetation. They also include information on stream flow and channel conditions.

By combining information about the land and the atmosphere, the system can project whether an intense storm is likely to stall over a specific area of the Front Range and how that could affect the flow of water on the ground.

"This new system is unique in that it provides a detailed forecast of the location and duration of a severe storm, as well as the watershed's likely response to the heavy rain," explains NCAR scientist David Yates. "Since flash floods are complex and fast-moving events, we need to know about both weather and ground conditions in order to predict them."