Hope versus sorrow: finding a frame for climate change

Dec 10, 2009 - by Staff

Dec 10, 2009 - by Staff

Bob Henson | 11 December 2009 • “You’re parachuting into a carnival,” an energy writer from Washington, D.C., told me yesterday morning as we arrived in Copenhagen. He’d been to nine of the Kyoto Protocol’s previous Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings, so I figured he knew whereof he spoke.

At first glance, the conference struck me not so much as a circus as much as an alternate universe—enormous, byzantine, and riddled with customs and folkways that weren’t at all obvious to someone who’s never been to a COP meeting. But you don't even have to set foot inside the security perimeter to realize something significant is going on.

The whole city is awash in eco-imagery, from the huge CO2 Cube outside the conference center—which represents the amount of space occupied by a metric ton of carbon dioxide at standard atmospheric pressure (about 8 meters or 25 feet on each side)—to the many public stages, scattered protests, and hundreds of billboards around town. The interest here and around the world is so intense that “Copenhagen” is reportedly the number-one search term on Google, bumping out “Tiger Woods.”

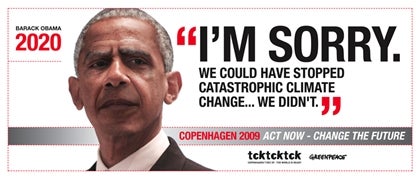

The longtime tension between scary scenarios of climate chaos and bright visions of a clean new world couldn’t be much more stark than it is on two competing sets of billboards. Strolling down the corridors of the Copenhagen airport, you can’t miss the series of visuals created by Greenpeace.

Each billboard shows a world leader as he or she might appear in the year 2020, along with the rueful message, “I’m sorry. We could have stopped catastrophic climate change . . . We didn’t.” It’s startling to see a gray-haired Barack Obama or an exhausted-looking Angela Merkel and contemplate a future that’s entirely plausible.

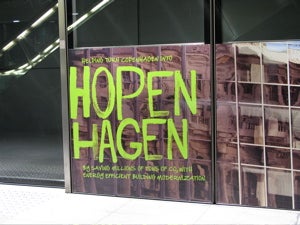

If you’d rather see the glass half full, switch your gaze to the Hopenhagen campaign, engineered by the United Nations (plus a few highly visible corporate sponsors). The paint-swash-style lettering provides a faint look of protest, but the messages are relentlessly upbeat: together, we are already changing how we work and live to address climate change, and we can do even more.

Depending on whom you’re trying to reach, there might be a role for both kinds of campaign. “Which message, which brand, which badge you like the best, that's a personal decision,” said one of the advertisers associated with the Hopenhagen campaign. “Ours is very focused on optimism and hope and is frankly less specific, so that people can interpret what it is they want to tell.”

Shocking ads can certainly grab attention. Those prematurely aged politicians did catch my eye, and they might give a few delegates pause before they head into negotiations. It's also chilling to see polar bears falling from the sky and smashing to the ground, as shown in a new television ad campaign from the activist group Plane Stupid designed to convey the climate hazard posed by short-haul flights. But over the longer term, a creepy ad may not be able to parlay the tension it generates into constructive action, according to Susi Moser, a former NCAR researcher.

With Lisa Dilling (University of Colorado in Boulder), Moser co-edited the landmark 2005 book Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change. Moser advises communicators who want to motivate action to “focus mostly on solutions” and to “help people envision a future worth fighting for,” rather than drowning them in science or scaring them with portents of climate catastrophe.

We'll find out in the next few days whether optimism or fear wins out in the plenary halls.