Taking a step back: Was Copenhagen a failure?

Jan 15, 2010 - by Staff

Jan 15, 2010 - by Staff

Bob Henson | 14 January 2010 • It’s been almost a month since the UN climate conference in Copenhagen lurched to completion, hobbled by a pack of competing agendas and irreconcilable differences.

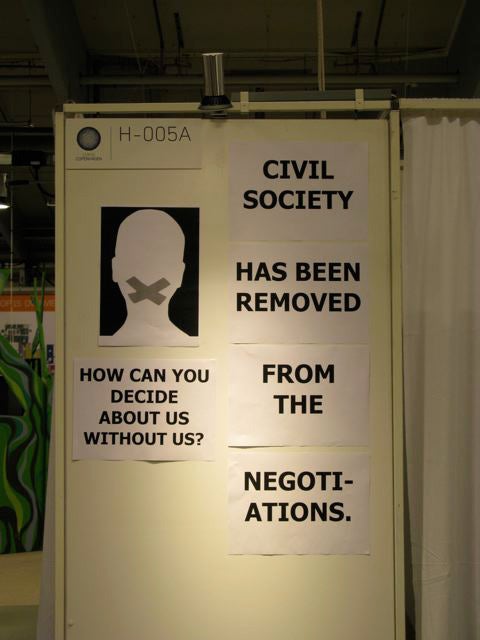

Under a dank, overcast sky on the meeting’s last day—18 December—the Bella Center was virtually devoid of the activists who had brought color and idealism to the proceedings. Most of the 22,000 registrants from nongovernmental organizations were shut out in the final two days to make way for heads of state and their vast security teams. While the NGO representatives carried on at an alternate venue, the exhibit halls were eerily quiet (see photo), the calm disturbed only by the occasional passage of a frazzled reporter or a harried delegate. Toward evening, two weeks of global negotiations culminated in an offsite meeting among the leaders of Brazil, China, India, South Africa, and the United States. From behind those closed doors emerged the bare bones of the “Copenhagen Accord.” Instead of a step beyond the Kyoto Protocol, the document was seen by many as a step backwards. Other countries were left out of the drafting process, and Kyoto-style binding targets were omitted (not that most countries were meeting their Kyoto goals anyhow).

Toward evening, two weeks of global negotiations culminated in an offsite meeting among the leaders of Brazil, China, India, South Africa, and the United States. From behind those closed doors emerged the bare bones of the “Copenhagen Accord.” Instead of a step beyond the Kyoto Protocol, the document was seen by many as a step backwards. Other countries were left out of the drafting process, and Kyoto-style binding targets were omitted (not that most countries were meeting their Kyoto goals anyhow).

Dissatisfaction among delegates was so widespread that, rather than formally adopting the document, the assembled parties managed only to “take note” of it. As summarized by the Pew Center on Global Climate Change, the four-page document (PDF)—posted on the UNFCCC website—includes the following:

Pages 4 and 5—the placeholders for specific mitigation pledges from each country—are currently blank. They’re to be filled in by 31 January.

A few participants and observers saw real progress in the accord. “We have come a long way,” said British prime minister Gordon Brown. The document is “politically important,” stressed UNFCCC director Yvo de Boer. Maldives president Mohamed Nashed said, “We did our best to accommodate all parties. We tried to bridge the wide gulf between different countries. In the end we were able to reach a compromise.” The Economist magazine noted that China and other developing nations agreed in principle to international emissions monitoring for the first time: “That is a crucial concession.”

These voices competed with a chorus of critics, painfully apparent in a succinct BBC roundup. “The accord was “nothing short of climate change skepticism in action,” said Sudan’s Lumumba Di-Aping, chief negotiator for the G77 group of developing countries. “Copenhagen ends in failure,” summed up the Guardian. Even the conference’s own news service acknowledged that “enthusiasm for the Copenhagen Accord is scarce.” According to the New York Times, “it has left many of the participants in the climate talks unhappy.”

Dubbing Copenhagen a “fiasco” and a “foundering forum,” the Financial Times claimed that the big winners in the process were climate skeptics, China, and the Danish economy. The losers, according to FT: carbon traders, renewable energy companies, and the planet.

The outlook for 2010

With a new decade now under way, the emergence of a binding global agreement to cut emissions doesn’t exactly look imminent. The Copenhagen Accord will be fleshed out with country-by-country goals, albeit voluntary ones. The next UNFCCC Conference of Parties, now slated for late 2010 in Mexico City, might always see a breakthrough.

However, a great deal depends on Congress, which must sign off on any binding U.S. pledge (unlike many other countries, where such commitments can be made solely by the executive branch). With a bill having gone through the U.S. House, Al Gore has urged the Senate to pass its version by Earth Day (22 April). However, with their energies preoccupied by health care and other nagging worries, senators and representatives may put climate change on the back burner this spring. After that point, election-year campaigning moves to the front.

All of this adds to the urgency of mitigation efforts being undertaken on smaller scales—by cities, states, and regions, as well as by private companies hoping to save money as they reduce their carbon footprint. It also highlights the need for serious work on adaptation, including partnership efforts being coordinated by UCAR.

In addition, many observers, including the Economist, see potential in new kinds of international match-ups that, for better or worse, bypass the byzantine politics of UN plenary meetings. “The old order of developed versus developing has been replaced by more interesting alliances,” said Ed Miliband, Britain’s secretary for energy and climate. “You had conversations you just can't have in a larger multilateral setting," said U.S. negotiator Todd Stern of the smaller groupings that emerged toward the end of the Copenhagen meeting. "Going forward there will need to be some kind of analogous small-group focus.”

Clearly, the end of the Copenhagen conference isn’t the end of work on climate change—though, with regards to Winston Churchill, it might be the end of the beginning.