Putting the U.S. cold snap in context

Jan 15, 2010 - by Staff

Jan 15, 2010 - by Staff

Bob Henson | 15 January 2010 • Journalists pulled their cold-related headlines out of mothballs and had a field day in early January, as a series of Arctic intrusions swept across the central and eastern United States and much of Eurasia. While the winter weather was indeed widespread and noteworthy—in some places, the most intense in decades—you might have thought another ice age was at hand, judging from press coverage.

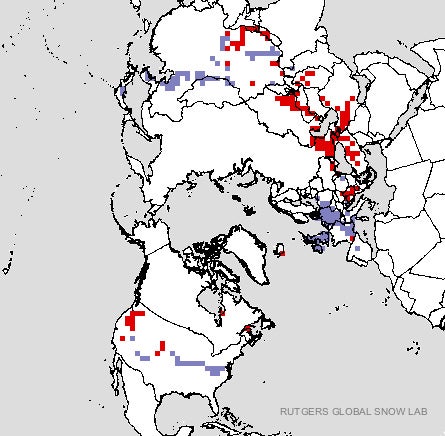

This graphic from the Rutgers Global Snow Lab shows where the extent of snow cover on 14 January was above average (purple) or below average (red), based on satellite-derived data. (Image courtesy Rutgers University Snow Lab.)

This graphic from the Rutgers Global Snow Lab shows where the extent of snow cover on 14 January was above average (purple) or below average (red), based on satellite-derived data. (Image courtesy Rutgers University Snow Lab.)

For example, Fox News asked, “Why Has Mother Nature Gone Bonkers?” The article went on to claim, “There are few precedents for the global sweep of extreme cold and ice that has killed dozens in India, paralyzed life in Beijing and threatened the Florida orange crop.” Now that temperatures are moderating in the hardest-hit areas, it’s fair to ask how unusual this spate of winter weather really was.

Certainly, just about every place that was struck has seen worse in the past. Few if any cities saw their coldest temperatures ever recorded, although some press reports gave a different impression by confusing daily record lows (the coldest ever observed on a particular date) with monthly or all-time lows. The bigger story in most places was not that the winter weather was unprecedented, but that it had been 20 to 30 years since such conditions had struck. That says as much about the climate in recent decades as it does about this particular winter.

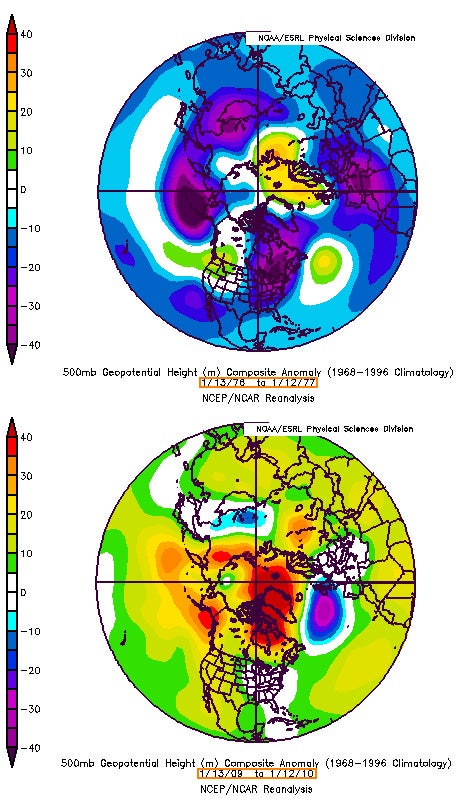

The charts above show global temperatures in terms of departures from average at the vertical midpoint of the atmosphere: the 500-millibar level, about 18,000 feet above sea level. At top is 1976–77, one of the coldest periods in recent decades; at bottom, 2009–10. Both periods included bouts of extreme cold at the surface, but the average temperatures at this height have warmed dramatically since the 1970s. (Images courtesy NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Division; comparison generated by Stu Ostro, The Weather Channel.)

The charts above show global temperatures in terms of departures from average at the vertical midpoint of the atmosphere: the 500-millibar level, about 18,000 feet above sea level. At top is 1976–77, one of the coldest periods in recent decades; at bottom, 2009–10. Both periods included bouts of extreme cold at the surface, but the average temperatures at this height have warmed dramatically since the 1970s. (Images courtesy NOAA/ESRL Physical Sciences Division; comparison generated by Stu Ostro, The Weather Channel.)

Even if the recent onslaught paled next to great winter outbreaks of the past, it was impressively persistent across some influential areas, including southeast England and the U.S. mid-Atlantic. Readings stayed seasonably cold across the Midwest and Great Plains with the help of a solid swath of snow cover, part of the Northern Hemisphere’s most extensive snowpack in 44 years of satellite record-keeping. Coupled with a strong north-to-south jet stream, the snow served as an air-conditioning unit for air masses heading south. For the United States as a whole, this past December was the coldest since 2000 and the 14th coldest since records began in 1895.

Consistency beat out intensity as the cold wave strengthened in early January across the mid-Atlantic and Deep South. Washington dropped below 40°F on New Year’s Day and didn’t climb above that mark until 13 January. Yet the coldest D.C. temperature during that stretch was 16°F, well above record territory. Likewise, several cities in Alabama saw their longest consecutive streaks of low temperatures below 25°F, even though no record lows were set. In Jackson, Mississippi, temperatures stayed below freezing for three days, leading to dozens of broken water mains.

Florida has been especially hard hit, as reinforcing pulses of cold air swept south for days on end. Even with sunshine, Miami could only manage a high of 48°F on 10 January, making it the city’s coldest day since at least 1989 (PDF). The most impressive single reading in the Northern Hemisphere may have been in Key West, Florida, which dipped to 42°F on 11 January. That was the second coldest reading in Key West’s entire 137-year weather record, beaten only by 41°F in 1873 and 1981. By comparison, readings out of Sweden and Siberia—though admittedly frigid—were well short of those regions’ all-time records.

One reason this outbreak was so amply covered by the press is that it struck highly populated areas: eastern Asia, eastern North America, western Europe. Meanwhile, other parts of the Northern Hemisphere—in particular, Greenland and the Arctic—have been unusually mild, even if fewer people were there to notice. Andrew Freedman made this point in a Capital Weather Gang post this week, as did the UK Met Office. “It's evident that the cold conditions in some of the world's major media centers was balanced out by warm conditions outside of, say, CNN's typical domain,” Freedman noted.

The warm and cold anomalies mesh well with the expected impacts from the negative phase of the Arctic Oscillation, which hit near-record lows (as discussed last week in this column).

A full-fledged January thaw looks set to sweep across the United States in the next few days, as heavy rains driven by El Niño slam into California. It’ll be interesting to see whether any U.S. cities experience warmth that’s as anomalous as the recent cold—and, if so, whether anyone notices.