Scientists pinpoint sources of Front Range ozone

Motor vehicles, oil and gas operations are top local contributors

Oct 30, 2017 - by Staff

Oct 30, 2017 - by Staff

BOULDER, Colo. — A comprehensive new air quality report for the state of Colorado quantifies the sources of summertime ozone in Denver and the northern Front Range, revealing the extent to which motor vehicles and oil and gas operations are the two largest local contributors to the pollutant.

The new report, based on intensive measurements taken from aircraft and ground sites as well as sophisticated computer simulations, also concludes that unhealthy levels of ozone frequently waft up to remote mountain areas, including Rocky Mountain National Park.

Scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) wrote the report with support from colleagues at NASA, drawing on a pair of 2014 field campaigns that tracked both local and distant contributors to pollution on the northern Front Range. The research was funded by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), NASA, and the National Science Foundation, which is NCAR's sponsor.

"We found that, on high ozone days, a critical portion of the ozone pollution here on the Front Range is the result of local activities, especially traffic and oil and gas operations," said NCAR scientist Gabriele Pfister, an author of the new report. "The pollution doesn't just affect the metro area. Prevailing daytime winds often transport the ozone to the west, exposing the foothills and mountains to high ozone levels."

Scientists involved in the 2014 field campaigns have published some of the findings in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

The report is designed to provide information to the CDPHE, which is working to reduce unhealthy levels of ozone in the Northern Colorado Front Range Metropolitan Area that stretches from Denver's southern suburbs to Fort Collins.

“The NCAR analysis provides important information that helps inform our ongoing efforts to better understand ozone formation and craft cost-effective strategies to reduce ozone levels and protect public health,” said Larry Wolk, executive director and chief medical officer at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

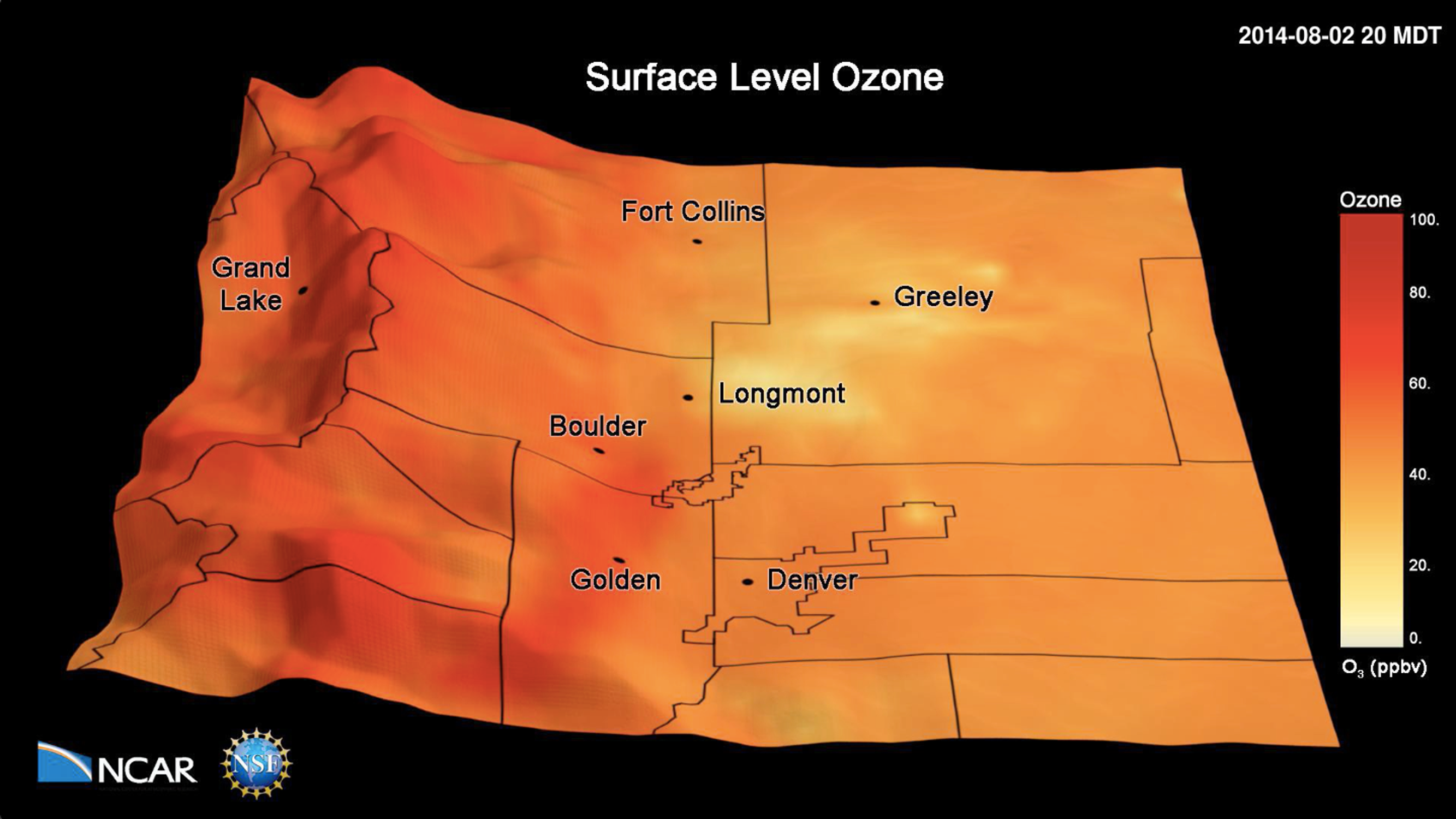

This visulization of surface ozone across the Front Range on an August afternoon shows how ozone pollution can sometimes be more accute in the high mountains than on the populated plains, depending on local winds. (©UCAR. This image is freely available for media & nonprofit use.)

This visulization of surface ozone across the Front Range on an August afternoon shows how ozone pollution can sometimes be more accute in the high mountains than on the populated plains, depending on local winds. (©UCAR. This image is freely available for media & nonprofit use.)

Tracing an invisible gas

An invisible but harmful pollutant, ground-level ozone can lead to increased asthma attacks and other respiratory ailments, producing symptoms that include coughing, trouble breathing, and chest pain. It also can be damaging to vegetation, including crops.

Ozone can be challenging to trace because it is the product of other pollutants. It forms in the atmosphere from chemical reactions of hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide in the presence of nitrogen oxides and sunlight. It peaks during the summer, when sunshine is most abundant.

Denver has a background ozone level of about 40-50 parts per billion (ppb) that is generated by numerous sources outside of the region. With the additional ozone generated by local emissions, the area on summer days often exceeds the federal health standard, which is set at an average of 70 ppb over an eight-hour period.

The report finds that cars, trucks, and other motor vehicles are the primary local contributors to ozone in the heavily developed urban corridor that stretches from Denver's southern suburbs to about the city of Boulder. Further north, however, emissions from oil and gas operations are the primary local contributors to ozone between Boulder and Fort Collins. Motor vehicles and oil and gas operations each contribute, on average, 30-40 percent to total local ozone production in the region on days when ozone exceeds the health standard, the report states.

Depending on prevailing winds, the air masses from the southern and northern parts of the metro area sometimes mix, enabling emissions from a variety of sources to produce ozone more readily. These sources include power plants, industrial facilities, and Denver International Airport.

The scientists warned of the potential for more ozone pollution to accompany expected population increases.

"The Denver metropolitan area will keep growing," said NCAR scientist Frank Flocke, a co-author of the report. "Total miles driven will keep increasing."

However, computer simulations run by the research team indicated that lowering local emissions could result in substantial ozone reductions. In some scenarios, ozone could be reduced by 6-10 ppb, which could make the difference between meeting or exceeding the national ambient air quality standards for ozone.

Leveraging two research projects

The report was commissioned as part of a major field project in the summer of 2014 led by Pfister and Flocke. The Front Range Air Pollution and Photochemistry Experiment (FRAPPÉ) relied on specially equipped aircraft, mobile radars, balloon-mounted sensors, and advanced computer models to measure emissions from industrial facilities, power plants, motor vehicles, agricultural operations, oil and gas drilling, fires, and other human-related and natural sources.

The FRAPPÉ team coordinated with a NASA-led air quality mission that took place on the Front Range at the same time: DISCOVER-AQ (Deriving Information on Surface Conditions from Column and Vertically Resolved Observations Relevant to Air Quality).

Colorado, like other states, relies on a limited number of ground-based stations to monitor air quality and help guide statewide policies and permitting. The field projects provided a much more detailed and complete, three-dimensional picture of the processes that affect air quality, including conditions far upwind and high up in the atmosphere.

The new report recommends additional monitoring of pollutants that lead to ozone formation at key ground sites. It also recommends comprehensive aircraft studies in the future to monitor air quality along the Front Range as the population increases and emissions sources change.

The report, "Process-Based and Regional Source Impact Analysis for FRAPPÉ and DISCOVER-AQ 2014," was submitted to the CDPHE in July and published online earlier this month.