A record winter during the American Revolution almost put independence on ice

A key moment in history highlights the importance of today's research into seasonal forecasts

Dec 18, 2017 - by Staff

Dec 18, 2017 - by Staff

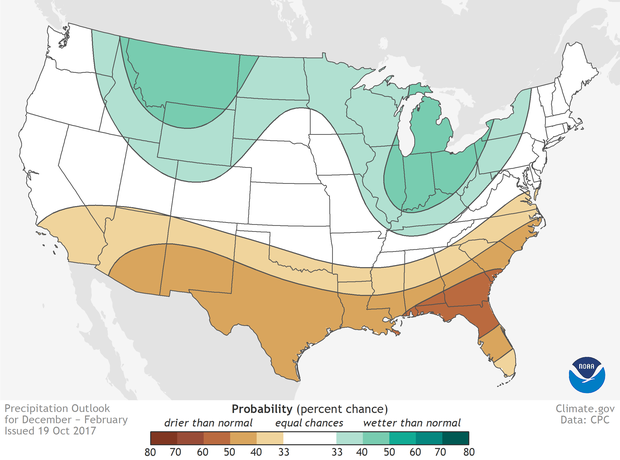

December 18, 2017 | The seasonal forecasts are in for this winter, and they generally indicate relatively average conditions across much of the country's midsection, with wetter-than-normal weather likely in the north and dryness in the South.

Continuing to improve these longer-term forecasts can help communities and businesses prepare for particular weather patterns — and possibly even save lives.

In fact, a good seasonal forecast could even have made a difference during a critical moment in the American Revolution.

This National Park Service painting portrays conditions at the Continental Army's New Jersey encampment in the winter of 1779-80, with a hospital hut in the foreground. (Image from Morristown National Historic Park.)

No East Coast season on record was colder than the winter of 1779-80. All of the saltwater inlets, harbors, and sounds of the Atlantic coastal plain froze over from Canada to North Carolina, remaining closed to navigation for a month or more for the only time in recorded history.

The winter happened to occur during the height of the Revolutionary War. George Washington and his soldiers were greeted by a foot of snow that already lay on the ground in November 1779 when they began arriving at their winter quarters outside Morristown, New Jersey.

The ensuing winter months almost cost the young nation its independence. The Continental Army was hammered by repeated snowstorms, including a blizzard in early January that dumped four feet of snow. Many of the soldiers lacked coats, shirts, shoes, and even food.

As the winter wore on, the soldiers became more embittered and mutinous than during the storied but milder winter two years earlier in Valley Forge. If not for help from surrounding communities during the winter of 1779-80, they may have deserted or even starved to death, potentially changing the course of history.

Longer-term forecasting in the two-week to three-month range is one of the most difficult challenges in meteorology. These subseasonal to seasonal forecasts, while providing general guidance, still lack much precision.

This winter, for example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts that the chances are roughly equal for conditions that are wetter or drier than normal across large swaths of the mid-Atlantic. Even a forecast of a wetter-than-average winter could play out in many ways, from a series of light rains to a couple of blockbuster snowstorms.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's forecast for wintertime precipitation, released in October, projects drier-than-normal conditions in the South and wetter-than-normal conditions in parts of the North. Click here for an analysis of the forecast by NOAA's Climate Prediction Center, as well as a forecast map that includes Alaska and Hawaii.

To add more detail to such forecasts, scientists are working to better understand the links between U.S. weather patterns and large-scale atmospheric and oceanic conditions, such as El Niño and the North Atlantic Oscillation (more popularly known as the "polar vortex" when it ushers in cold weather).

Recognizing the importance of such research, Congress in April passed the Weather Research and Forecasting Innovation Act, a major weather bill that calls for more work into subseasonal to seasonal prediction.

If the modern understanding of the atmosphere and oceans had existed during the American Revolution, perhaps Washington and his soldiers could have taken more precautions. The next time the nation is threatened by an unusually severe winter, better forecasts may make it possible to prepare.

"Scientists are gaining new insights into the entire Earth system in ways that will lead to predictions of weather patterns weeks, months, or even more than a year in advance," said UCAR President Antonio Busalacchi. "History shows this type of intelligence can be critical to national security, as well as to businesses and vulnerable communities."

Writer/contact: David Hosansky

Manager of Media Relations