Cold facts of air pollution

WINTER field project examines cold-season air quality

Feb 2, 2015 - by Staff

Feb 2, 2015 - by Staff

February 2, 2015 | The difference between a breath of cold air and a breath of warm air isn’t just the temperature. It’s also the pollutants they might contain.

Until now, wintertime air pollution hasn’t been studied in much detail. Scientists have focused more on warm air, partly because summertime's stagnant atmospheric conditions and intense sunshine tend to worsen ozone pollution. But that's about to change as researchers turn their attention to winter air quality in the eastern United States.

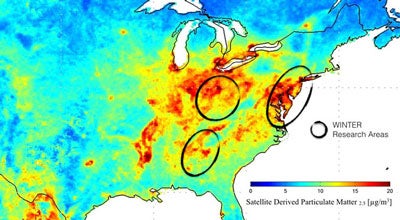

The WINTER field project will focus on the Northeast urban corridor, Ohio River Valley, and Southeast Mid-Atlantic. (©UCAR. Image by Alison Rockwell, NCAR, based on NASA satellite map. This image is freely available for media & nonprofit use.)

This month, a major air quality project known as WINTER (Wintertime Investigation of Transport, Emissions, and Reactivity) takes to the air to examine pollutants across the Northeast urban corridor, Ohio River Valley, and Southeast Mid-Atlantic. Scientists will home in on wintertime emissions from urban areas, power plants, and farmland, and seek to better understand the chemical processes that take place as pollutants move through an atmosphere that is not only colder but also darker than in summer.

The field campaign, which runs from February 1 to March 15, is being led by scientists at the University of Washington, NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory, University of California Berkeley, Georgia Institute of Technology, University of Colorado Boulder, and the University of New Hampshire. The research team will use the NSF/NCAR C-130, a flying laboratory equipped with more than 20 instruments to measure gases and particles.

The aircraft is owned by the National Science Foundation and operated by NCAR. NCAR is also managing the project, including coordinating research flights and providing data services. Flight operations will be based at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

"Aircraft missions will occur at different times during the campaign so that the pollutant gases and reactions can be observed during the day, at night, from night into day, and day into night,” said NCAR project manager Cory Wolff.

NCAR scientist Alan Hills (right) and University of California, Irvine, graduate student Jason Schroeder operate instruments for the WINTER field project aboard the NSF/NCAR C-130. (©UCAR. Photo by Alison Rockwell, NCAR. This image is freely available for media & nonprofit use.)

A number of factors affect wintertime air: colder temperatures, snow cover, lower absolute humidity, and fewer hours of sunlight. Plants tend to emit fewer chemicals, while people may emit more as they burn heating oil and other fuels to heat their homes. In addition, pollutants may travel farther because chemical reactions take place more slowly in cold air.

By flying over several regions, the WINTER research team will better understand the atmospheric impacts created by different types of emissions from major cities in the Northeast and coal-fired power plants in the Ohio River Valley. The scientists will compare those emissions with data they gather in the Southeast, where winters are milder, plants have a more pronounced influence on the atmosphere, and emissions come from agricultural burning.

The project’s findings will be used to provide more detailed information to decision makers and improve computer models of the atmosphere.

“Wintertime pollution has not been the focus of many campaigns—most are during the spring and summer months when the Sun has maximum impact,” said Wolff. “By sampling the air in the cold and darkness of winter, the science team can get a better sense of the atmospheric chemistry of the eastern United States and compare that to other times of year. "

Writer/contact

David Hosansky

Collaborators

University of Washington

NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory

University of California Berkeley

Georgia Institute of Technology

University of Colorado Boulder

University of New Hampshire

Funders

National Science Foundation (NSF)

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)