Hurricane study to tackle long-standing mystery

Jul 20, 2010 - by Staff

Jul 20, 2010 - by Staff

News Release

BOULDER—Scientists are launching a major field project next month in the tropical Atlantic Ocean to solve a central mystery of hurricanes: Why do certain clusters of tropical thunderstorms grow into the often-deadly storms while many others dissipate? The results should eventually help forecasters provide more advance warning to those in harm’s way.

“One of the great longstanding mysteries about hurricanes is how they form,” says Christopher Davis, a scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and a principal investigator on the project. “There are clusters of thunderstorms every day in the tropics, but we don’t know why some of them develop into hurricanes while others don’t. We need to anticipate hurricane formation to prepare for hazards that could develop several days later.”

PREDICT, the Pre-Depression Investigation of Cloud Systems in the Tropics, will run from August 15 to September 30, the height of hurricane season. The project is funded primarily by the National Science Foundation (NSF), NCAR’s sponsor.

In addition to NCAR, collaborators include the Naval Postgraduate School; University at Albany-SUNY; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; University of Miami; NorthWest Research Associates, Redmond, Washington; New Mexico Tech; Purdue University; and University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Based on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, PREDICT will deploy the NSF/NCAR Gulfstream V research aircraft. The G-V jet, also known as HIAPER, has a range of up to 7,000 miles and will reach an altitude of about 43,000 feet, enabling scientists to take observations near the tops of storms that form thousands of miles from the coast. (View the G-V's external instrumentation for PREDICT.)

By better understanding the formation of tropical storms that may become hurricanes, scientists can help the National Hurricane Center attain the goal of seven-day hurricane forecasts, rather than the current limit of five days. Long-term predictions are needed by shippers, offshore oil operators, emergency managers, and others involved in public safety to better prepare for incoming storms.

Currently, many storms develop too quickly for society to make sufficient preparations. In 2007, for example, scattered thunderstorms in the Atlantic Ocean organized into a larger-scale storm system that quickly grew into Hurricane Felix, a category 5 storm that caused widespread loss of life and destruction in Nicaragua and Honduras.

The PREDICT flights will be coordinated each day with flights for two other hurricane studies taking place this summer. NASA is leading a project known as GRIP (Genesis and Rapid Intensification Processes), while the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is leading IFEX (Intensity Forecasting Experiment).

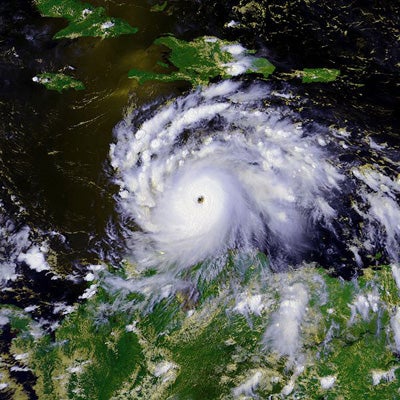

A cluster of thunderstorms took just a few days to build into Hurricane Felix in 2007. By the time of this satellite image—1810 UTC (2:10 p.m. EDT) on August 2—Hurricane Felix had winds exceeding 130 mph. (Image courtesy NOAA Satellite and Information Service, via Wikipedia.) More images are available in the PREDICT Multimedia Gallery.

Although the three projects are independent, their observations have the potential to capture the complete evolution of one or more hurricanes from formation until landfall, as well as capture non-developing storms that are equally important for understanding why some disturbances develop beyond the wave stage while many others do not.

“We hope the information we gather this summer will unlock some of the secrets of how hurricanes form and evolve,” Davis says. “This is key information we all need to better protect lives and property from major storms.”

One of the central goals of PREDICT is to pinpoint the differences between a tropical thunderstorm cluster that is capable of growing in power and one that is likely to weaken.

Scientists theorize that part of the secret may lie in the 3-D air motions within a larger system, such as a tropical easterly wave or a subtropical disturbance, that can serve as a safe haven for rotating thunderstorms. As these thunderstorms draw in rotating air from their sides, they can develop increasingly powerful, tightly wound circulations, analogous to figure skaters who spin faster and faster by drawing their arms inward. In contrast, strong downdrafts that reach the surface and spread out can slow the spin of the storm. When a thunderstorm cluster is surrounded by a deep layer of moist air, the likelihood of downdrafts is significantly reduced.

But the problem of hurricane formation is not as simple as the formation of one or several rotating thunderstoms, which persist typically for a few hours at most. To unlock the mystery one must look also at the larger-scale environment, including the structure and composition of the large-scale disturbances and tropical easterly waves that encompass clusters of thunderstorms.

PREDICT will focus on regions where tropical easterly waves and embedded thunderstorm complexes are most likely to form tropical storms. The project will gather data across areas as large as 500 by 500 miles, using remote sensing instruments on NOAA and NASA aircraft to probe for details within these preferred regions of development.

Some scientists have advanced a concept, known as the “marsupial pouch,” that they believe is key to tropical cyclone development. According to this hypothesis, if a storm cluster moves at a similar speed to the surrounding flow in the lower to middle troposphere and is not adversely deformed by horizontal wind shear, then it is largely protected from being torn apart. This protective environment, known informally as the “marsupial pouch,” can also help insulate storms from dust and dry air that might impede their growth. Within such a protective pouch, the system could draw energy from warm ocean waters, develop a closed circulation of winds, and form a tropical depression, perhaps eventually becoming a tropical storm or hurricane.

“We think the marsupial pouch provides a focal point or ‘sweet spot’ where favorable conditions could persist for several days and where rotating thunderstorms are most likely to aggregate into a larger-scale storm,” says Michael Montgomery, a PREDICT principal investigator and lead scientist, as well as a professor at the Naval Postgraduate School. “This would dramatically increase the chances of a tropical depression or larger storm forming.”

The findings from PREDICT will be particularly useful for forecasts in the North Atlantic. However, the results will also help forecasters in parts of Asia and Australia where coastlines are vulnerable to typhoons and cyclones (as hurricanes are known there). The findings may also help provide important insights into the equally difficult question of whether climate change will significantly increase the frequency or intensity of these powerful storms.

“If we can better understand the processes that lead to hurricanes, we can apply that knowledge to our changing climate and how it is likely to influence future tropical storms and hurricanes,” Davis says.

Part of the reason that hurricane formation has remained such a mystery is that scientists have comparatively little information in general about storms that develop over the ocean. Observations from ships and aircraft are few and far between, while satellites have difficulty providing wind and temperature information beneath cloud tops within a storm.

The PREDICT research team will fly near thunderstorm complexes and probe the surrounding environment once or twice per day when tropical systems of interest come within about 1,500 miles of St. Croix. Using dropsondes (parachute-borne instrument packages) and a variety of other instruments, they will take measurements of temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction, and water vapor. They will also gather fine-scale details of clouds, including ice particles and water droplets. One of the main goals is to take measurements of airborne Saharan dust and associated dry air that can interfere with hurricane formation.

“We’ll be scrutinizing developing storms on many scales, from the invisible to the enormous,” says Lance Bosart, a professor at the University at Albany-SUNY. The airborne observations will be compared with data gathered from satellites as well as from ground-based radars in the Caribbean.