A close-to-home wildfire

Sep 9, 2010 - by Staff

Sep 9, 2010 - by Staff

Margaret LeMone | 9 September 2010 • I have always been fascinated by fires. My last career ambition before I decided on a career in weather was to be a firefighter. My first atmospheric field program was an investigation of simulated controlled burns near Bend, Oregon, where I learned a little bit about how fires interact with weather.

Photo 1. Around 10:15 a.m. MDT on Monday, 6 September, near Allenspark, Colorado.

The subject has been on my mind again over the last few days, as life in Boulder, Colorado, has been dominated by a major fire to the west of town that has destroyed at least 169 homes. Now dubbed the Fourmile Fire, it began in Fourmiile Canyon a few miles west of Boulder on Labor Day, 6 September.

That morning, my husband and I decided to go hiking in Rocky Mountain National Park, at a site recommended by a local birder. We got up early, and entered the park near Allenspark at around 8:00 a.m. (See map at bottom left.) The first few hours, spent on trails near the park entrance, were pleasant, and we enjoyed watching the nuthatches busily eating among the ponderosa pine, the goldfinches flying over the meadow, and the wrens chattering near the creek.

Things changed when we started hiking up Wild Basin Trail. The winds became strong, and the birds were apparently absent – hunkered down somewhere out of the wind. Around 10:30 a.m., choking on dust lifted from the trail and the nearby dry soil, we decided to go back downhill, hoping to get out of the wind. But even near the park entrance where we had started hiking, the winds were so strong that it was hard to open the car door, and, at times, even to stand up.

We abandoned the park and headed for the nearby town of Allenspark for lunch. Immediately, we saw a smoke plume ahead of us (see Photo 1). We pulled off the road so I could photograph it. Obviously a vigorous wildfire was in progress. We were not surprised: a red flag warning had been issued because of the expected strong winds, dry air, and the dry surface. Much of the area hasn’t received rain in weeks, and the relative humidities that morning were in the single digits.

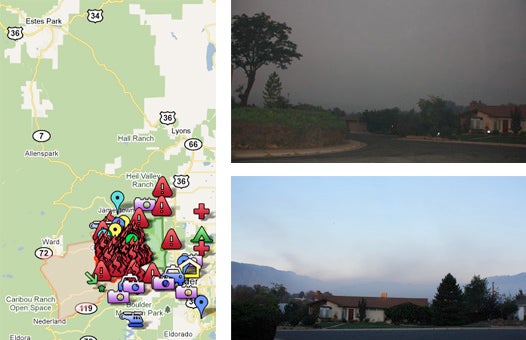

Photo 2. Around 1:00 p.m. on 6 September, looking south along U.S. 36 between Lyons and Boulder. Note the wavelike features on top of the plume, which resemble Kelvin-Helmholtz clouds.

Photo 3. Satellite imagery from 6 September taken at 1:03 MDT (left) and 5:03 MDT (right) shows the wildfire plume as a narrow tongue extending eastward from the Boulder foothills. (Courtesy http://www.rap.ucar.edu/weather.)

Photo 5. The smoke plume from my office window at NCAR’s Foothills Lab, looking northwest, at about 2:00 p.m. MDT on Tuesday, 7 September.

The restaurant we visited in Allenspark didn’t take credit cards, so we stopped in Lyons for lunch, watching the smoke plume to our south from the restaurant patio. While the plume near the fire showed the cauliflower structure of a convective cloud, the plume farther downstream looked more like the flow of water downstream from a rock – relatively smooth on top, with some evidence of wavelike features (Photo 2, left).

After lunch, we drove through the plume – not a pleasant experience. Unfortunately, the smoke extended into Boulder, so we kept the windows of our house in north Boulder shut through the afternoon, even though it appeared we were at about the southern edge of the plume. The plume stretched to the east as far as the eye could see. In fact, it was easily visible from space, as can be seen from the 1:00 p.m. MDT satellite image (Photo 3, left side). As the afternoon progressed, the plume rode the strong winds eastward, reaching Nebraska by 5:00 p.m. MDT (Photo 3, right side).

When smoke lays down

That evening, something interesting happened. The air near the ground became clear of smoke, even though glowing smoke was still obvious until 10 p.m. when I last checked. We figured that the ground in Boulder had cooled enough so the smoky air from the foothills couldn’t mix down to the ground. Besides, we knew that fires “lay down” at night and burn less intensely as temperatures cool, relative humidities rise, and winds die down. Nonetheless, we kept our windows closed – except for those in the bedrooms.

This was a mistake. By early morning, the smoky air had worked its way down to our part of Boulder (Photo 4, at bottom). My suspicion is that this was normal evening drainage flow: the air on the ridges cooled, and, being denser than the surrounding air farther from the surface, flowed downhill into Boulder. The inversion that had protected us early now kept the smoky air trapped in town. In fact, the firefighters had to wait for the smoke to clear so that they could effectively fight the fire on Tuesday.

Once the ground over Boulder warmed, the smoke mixed vertically, giving us some relief by Tuesday afternoon. But it was clear that the fire was still burning vigorously. From the NCAR Foothills Laboratory in northeast Boulder (Photo 5, left), we watched the main plume and a second one to the south as the fire-fighting aircraft flew in and out of the region.

A trip to Denver to watch the Colorado Rockies play baseball gave us a chance to experience some fresh air. When we returned, we were pleased to note a lack of glowing smoke. But the air was smoky in Boulder, so we kept our windows closed.

By Wednesday, the early-morning visibility had improved (Photo 6, below), and Boulder seemed almost normal. But it was worse elsewhere. A colleague reported a thick plume of smoke following the Boulder Creek valley to the south of us – again, night-time cooling of the air on the ridges produced dense air that flowed downhill. South of the creek, it was relatively clear.

Fortunately, the weather on Wednesday helped the firefighters. The air was moister, and clouds appeared by noon. By mid-afternoon, the skies were cloudy, and a gentle, light rain started falling around 4 p.m. From our offices, we had to look for the fire, revealed only by haze between the foothills, and a nearly translucent broad smoke plume from the burn area. By the end of the day, the fire was 10% contained. However, the coming days would see a continuing struggle against the fire and the elements, which were not to remain so friendly. As I write this, a new round of warm, dry, windy weather is approaching.

Photo 4 (top right): Around 6:30 a.m. on Tuesday, 7 September, looking southwest toward the foothills (slightly over a mile away).

Photo 6 (bottom right): Around 7:00 a.m. on the morning of Wednesday, 8 September, taken from close to the same spot as Photo 4, except roughly a half-hour later and looking more toward the west. Note how much sharper the foothills appear.

Left: Map of Boulder County with Fourmile Fire area outlined in orange and core fire area indicated by flames. The author drove from Boulder to Rocky Mountain National Park (just past the top left corner of map) via US Highway 36 to Lyons and CO Highway 7 through Allenspark, returning along the same route. (Map courtesy of a cooperative project drawing on Google Maps.)