Rivers, lakes, and snow: A devil of a problem

Mar 10, 2011 - by Staff

Mar 10, 2011 - by Staff

Bob Henson | 10 March 2011 • Two very different kinds of flooding are in store for parts of North Dakota and Minnesota over the coming months. One has gotten a fair bit of attention from national media. The other is less well known but even more intriguing. Both are related to a climate flip-flop that has no end in sight—and no end to the headaches for folks in the upper Midwest.

The Grand Forks Herald building lies in ruins a few days after fire and flood devastated the North Dakota city's downtown area in 1997. (Courtesy FEMA/Phil Cogan/Wikimedia Commons.)

The better-known tale is the latest installment in a soggy franchise: The Red River of the North Runs Wild. Serving as the border between North Dakota and Minnesota, this river is virtually unique among its U.S. counterparts in that it runs almost due north for more than 300 kilometers (190 miles). Snow piles up during the region’s long, harsh winter. When the spring thaw finally hits, the melting typically works its way from south to north. This means that flood waters run into ever-worsening traffic jams of ice as they stream toward Manitoba.

The riverside city of Grand Forks, North Dakota, was devastated by record flooding in 1997 that led to surreal scenes of downtown buildings ablaze while surrounded by water. Further south, the state’s biggest city, Fargo, barely escaped a similar fate in the spring of 2009 when record floodwaters struck there. The spring of 2010 brought more high water along the Red River, and this year looks ever worse. New projections issued on 4 March give the Red a roughly one-in-three chance of topping its 2009 record of 40.84 feet at Fargo (see the “conditional simulation” graph on this chart).

Two main factors play into a given spring’s flood risk along the Red. One is the amount of snowfall in place as spring arrives. Overall, it’s been a snowy winter for the region, with the December–February period ranking among the wettest of the last century. The other big element is timing. If spring unfolds gradually and dryly, there’s much less risk of flooding than if it’s a wet season with a rapid switch from cold to warm.

It’s too soon to know exactly how things will play out this spring. Flood levels are notoriously difficult to peg, with so many variables at play. But locals aren’t taking chances. The twin cities of Moorhead, Minnesota, and Fargo are now in the process of filling four million sandbags.

Then there’s the bizarre case of Devils Lake. Sprawled across northeastern North Dakota, it takes in water from a region larger than Delaware. Like a creature from a hydrologic horror flick, the lake has been expanding off and on for 70 years, most dramatically from the mid-1990s onward. Some of its tendrils have blocked rail lines and roadways for years. A $100 million levee expansion (PDF) is on tap for the town of Devils Lake, and the idea of moving the entire town of Minnewaukan has been suggested.

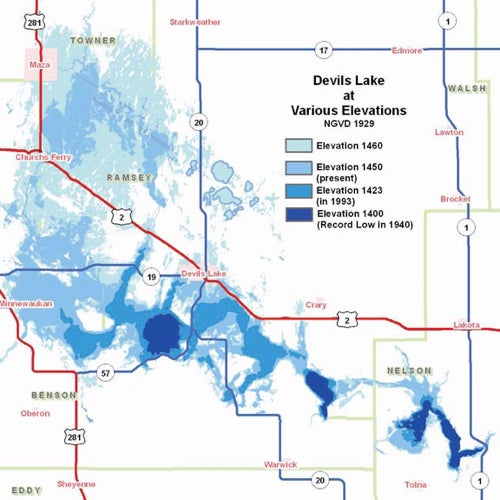

The problem is that there’s no regular channel leading out of Devils Lake. If water escapes, it’s into the air, through evaporation. When the water height reaches about 1,447 feet above sea level, the lake begins flowing into nearby Stump Lake (far lower right of map).

Because of the region’s relatively flat landscape, the surface coverage of Devils Lake expands dramatically as the lake level rises. (Courtesy North Dakota State Water Commission.

If the two lakes were to swell to around 1,458 feet, they’d begin pouring into the Sheyenne River and on east toward the Red. Nobody knows exactly how this would unfold, since it’s never happened in modern times. There may have been at least two such floods over the last 4,000 years, though, according to the North Dakota Geological Survey.

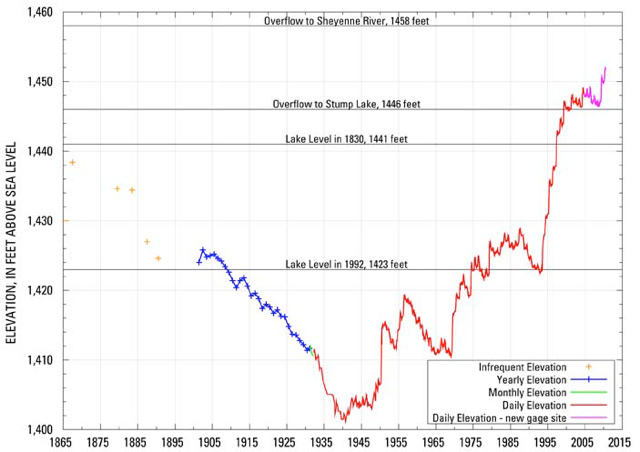

The earliest gauge reading for Devils Lake, taken in 1867, shows an elevation of 1,438 feet (see graph, below). By the end of the Dust Bowl, in 1940, heat and drought had turned the lake into a relative puddle. At that point, it covered only about 10% of its 1867 surface area. However, the lake slowly recovered over the following decades.

Then came a mysterious shift in the region’s climate. Starting around 1980, the average yearly precipitation near Devils Lake jumped from a little more than 400 millimeters (16 inches) to just over 500 mm (20 in). It’s remained on the higher side ever since. The shift may be related to a mid-1970s change in the Pacific Ocean and effects that reverberated globally.

It took awhile for the extra moisture to saturate soil and ponds in the vicinity. But by the mid-1990s, the water had nowhere to go but directly into Devils Lake, whose elevation jumped more than 20 feet in just a few years. The lake now spans about 520 square kilometers (200 square miles), which is roughly four times its size in 1993. The last 12 months haven’t helped: March-to-February precipitation was the heaviest on record for much of the Devils Lake basin.

Fiona Horsfall, who heads the Climate Services Division of the National Weather Service, has seen the quiet devastation first hand. “It was a shock,” she told attendees at a presentation she gave at the American Meteorological Society’s 2011 annual meeting in Seattle. “You see these street signs in the middle of the lake and you wonder what they’re doing there.” Horsfall showed conferencegoers a NOAA website, launched last July, that consolidates decision support for the region.

Road closures are just one of the many complications from the nonstop growth of Devils Lake in northeast North Dakota. (Courtesy U.S. Geological Survey.)

What happens next? NOAA predicts that Devils Lake will reach yet another record height this year. As for the longer term, the U.S. Geological Survey warns that the lake could expand for decades to come. Geologists point to evidence that, for thousands of years, the region has swung between long spells of “normal” climate and shorter wet periods, typically lasting several decades but sometimes the better part of a century. There’s no way to know how long any given soggy spell might last.

With this in mind, in 2010 the USGS’s North Dakota Water Science Center studied the lake’s future using a stochastic simulation model (PDF), one that employs varying end dates for the wet spell in the absence of a firm forecast. Overall, the study found a better-than-50% chance that Devils Lake will be higher in 2030 than it is now, but less than a 10% chance that it will have spilled toward the Red River (assuming no change in hydrologic engineering between now and then).

Lurking in the shadows of this monstrously growing lake is another spectre: that of human-induced climate change. Temperatures are projected to increase across the Great Plains in coming decades. If this comes to pass, higher evaporation rates could help keep the lake in check. However, precipitation is also projected to increase across most of Canada and the northern U.S. tier of states, according to the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. A 2010 assessment led by NOAA’s Martin Hoerling (PDF) found that the natural ups and downs of decadal variability—including the current prolonged wet spell—will play a larger role than anthropogenic climate change in shaping Devils Lake over the next few decades.

However you look at it, the devil—and the future of Devils Lake—lies in the details.

The height of Devils Lake now exceeds anything in modern records, which extend back to around 1900, with scattered gauge reports as far back as 1867. (Courtesy North Dakota State Water Commission.)