The other news from Britain: Heat and drought

May 12, 2011 - by Staff

May 12, 2011 - by Staff

Bob Henson | 17 May 2011 • Millions of eyes were on the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton last month, even as another major UK news story took shape—one dealing with meteorology rather than monarchy. The wedding weather on 29 April turned out fine, with no rain and even a few moments of sunshine. However, the month as a whole was perhaps a little too fine. It was, in fact, central England’s warmest April in at least 350 years (see more below), and one of the driest in decades.

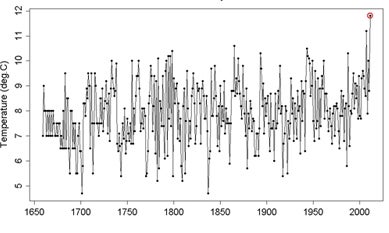

This year brought the warmest April by far in the Central England Temperature record, which averages readings from a set of long-term weather observing sites. (Illustration courtesy tamino.wordpress.org; here's a larger version of the graphic.)

Given the year’s global drumbeat of disaster, including the tornadoes that rampaged across the southeast United States last month, it’s hard to see London’s balmy spring as anything but splendid. Yet the persistent dryness and warmth across the United Kingdom and much of Europe could spell major trouble if it extends into late spring and summer.

At one station in the south London area, April brought only three days with measurable precipitation. Even the wettest of those days saw a mere 1.3 millimeters of rain (0.07 inches). For the UK as a whole, there was about 50% more sunshine than average, and it was the sixth driest April going back to 1910, according to preliminary data from the UK Met Office.

Temperatures were even more impressive. By a long shot, this was the warmest April in the venerable multi-station Central England Temperature record. The world’s oldest such dataset, it extends back to 1659. The CET is thoroughly vetted and adjusted for instrument changes, heat islands, and other potential biases, as explained in this 2005 study (PDF) led by David Parker (UK Met Office).

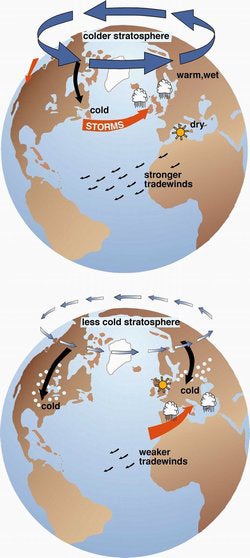

Schematic of the major features typically seen with the positive (top) and negative (bottom) modes of the Arctic Oscillation, also known as the Northern Annular Mode. (Illustration by John Michael Wallace, University of Washington, courtesy NSIDC Education Center.)

As evident in the graphic at right, April’s CET value of 11.9°C (53.4°F) smashed the previous April record, set only four years earlier, by a whopping 0.7°C (1.3°F)—a very significant margin for a monthly average. In Cambridge (1959–2011 data), April managed to be warmer than every May but one in the last half-century, with May 1992 standing as the record holder. Over a five-day stretch late in April 2011, temperatures in and around London topped 24°C (75°F) every afternoon, reaching the 26°C (79°F) mark in some spots.

The vivid contrast between the UK’s bone-chilling cold last December and this April’s warmth has distinct roots in the larger-scale atmospheric circulation. During the last two Decembers (2009 and 2010), the Arctic Oscillation (AO) and the closely related North Atlantic Oscillation were as strongly negative as ever observed in the last 60 years of records. In April 2011, though, the story was far different.

Typically, a powerful jet stream slices across the North Atlantic during wintertime, which pushes relatively mild and moist air into Europe (see graphic at left). A negative AO means that the north-south pressure differences that drive this jet stream are diminished. This allows cold air to spill more easily into Europe from the north and east. A strongly positive AO, on the other hand, intensifies the pressure differences and the associated jet stream flow, so that mild and wet conditions become more likely than usual.

Last month the AO averaged +2.275, according to this chart on NOAA’s AO website. That’s the highest reading for any April since records began in 1950. Even the three-month average for February–April 2011 is impressively high (see the time series below). Yet the Atlantic moisture across northern Europe and the UK that often accompanies a positive AO has been shunted even further north, leaving much of the continent unusually dry as well as mild.

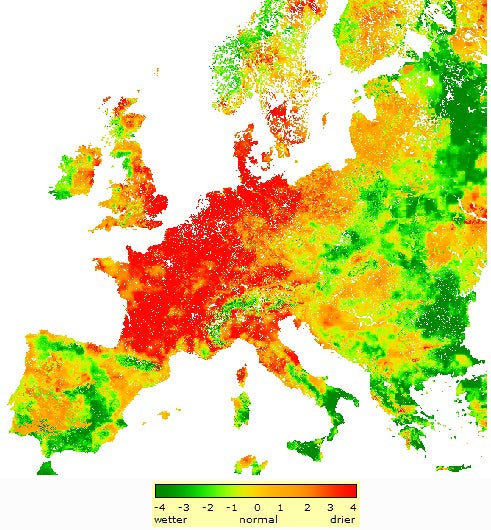

As noted by the European Drought Observatory in its summary of January–April precipitation, “Extended areas of France, Germany, Great Britain, Benelux, Denmark and Hungary have received less than 50% of the climatologically expected rain.” The dryness was especially pronounced in April.

When standardized to produce a three-month running mean, the Arctic Oscillation showed two strong dips in winter 2009–10 as well as a major peak in early 2011. The AO was also quite low in December 2010, but the drop was comparatively short-lived, so the three-month average shown here is less dramatic than that single-month value. (Image courtesy NOAA Climate Prediction Center.)

While the extra-low AOs over the last two winters got plenty of media attention, this spring’s extra-high AO has been virtually ignored. The oscillation is renowned for its hard-to-predict swings, so there’s no telling what it will do later this spring and summer. Thus far in May, it’s been weakly negative.

The parched soils across the UK and the heart of Europe are themselves a worrisome portent for the coming summer. As a rule, springtime dryness helps make a summer drought more intense than it would be otherwise. This is because dry land allows the energy from warm-season sunlight to go into heating the soil and air insetad of into evaporating moisture. A warm, dry spring also pushes plants to develop sooner, with the extra sunshine and lack of rain working to dry out the early greenery. Satellite imagery shows that northwest Europe’s ground is already quite thirsty, as illustrated in this BBC report from 9 May.

Erich Fischer is watching the situation unfold with keen interest. After a stint as an NCAR postdoctoral researcher, Fischer is now at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH Zurich).

“The present conditions are highly exceptional not only in the UK but all across western Europe,” says Fischer. Parts of central Europe saw less than 40% of their average precipitation for the period of February through April, according to a report posted by the World Meteorological Organization on 5 May (scroll to “Drought conditions in Europe 2011”). On a website at Switzerland’s meteorology agency (website text in Germany), graphics show that each month from January through April has seen precipitation totals far below average across the country.

In a 2007 paper for the Journal of Climate, Fischer and colleagues examined the connection between dry spring soils and the subsequent heat wave in the summer of 2003, which killed tens of thousands of Europeans. They conducted a set of modeling experiments to determine whether the 2003 heat wave would have been less intense had Europe’s soils started the summer with a typical amount of moisture. Using that starting point in the model, they found a reduction of about 40% in June-to-August temperature anomalies for 2003.

Of course, the currently parched soil doesn’t guarantee that a long-lived zone of high pressure (an anticyclone) will set up during the hottest time of the year. “There is clear observational evidence for dry springs that were not followed by hot, dry summers,” notes Fischer. “It still takes a persistent anticyclonic anomaly in summer to produce an extreme summer drought and heat wave.”

Seasonal-scale climate models still have trouble capturing the mix of factors leading to events such as the 2003 heat wave, as explained by Antje Weisheimer (European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) and colleagues in a recent study for Geophysical Research Letters. However, progress is being made. In a retrospective “hindcast,” an upgraded version of ECMWF’s seasonal model dubbed CY33R1 was able to predict the 2003 heat wave by mid-spring (1 May).

Weisheimer and colleagues credit the progress to improved land-surface hydrology in the model, as well as enhanced convection and radiation schemes: “In our case, the combination of all three proved key to the successful retrospective predictions of this record-breaking event.”

Soils across the heart of western and northern Europe are far drier than usual, as indicated in this graphic showing conditions on 10 May 2011. The anomalies are calculated by comparing daily soil moisture data from the European Commission to a 15-year record. (Image courtesy European Drought Observatory.)