Texas–Oklahoma drought: What next for the Southern Plains?

Sep 20, 2011 - by Staff

Sep 20, 2011 - by Staff

Bob Henson | 20 September 2011 • It finally rained in Pecos. On 14 September, the West Texas town received a modest but welcome 0.13 inches, plus another 0.27” in the following three days (about 16 millimeters total) . Normally that wouldn’t be big news—except the last time Pecos had gotten any substantial rain was on 23 September 2010. During the intervening year, the town scraped by with a mere 0.03” (1 mm).

Fire devoured much of the forest in Bastrop State Park just east of Bastrop, Texas, on 9 September. (Photo © 2011 K. West.)

The beneficial rains of the last week—an inch or more across much of Texas and Oklahoma—are a blessing for locals, but they’re only a few drops in the bucket next to the record drought and heat that’s ravaged the region since last autumn.

The drought’s toll on people, crops, livestock, and the landscape is obvious in a stunning photo blog recently assembled by the Austin American-Statesman, and in the equally powerful comments from readers. One wrote: “I live in Omaha, Texas, and every afternoon I drive home and count more limbs dropping off trees.”

Not far from Austin, a catastrophic fire consumed more than 1,000 homes in Bastrop County earlier this month. I bicycled along quiet, tree-lined roads in Bastrop State Park on a November afternoon five years ago, amid a patch of evergreen forest similar to the Piney Woods of East Texas that was dubbed the Lost Pines. Now many of those pines are truly lost, with more than 95% of the park’s acreage burned.

No relief in year two?

The nonstop 100-degree days are gone, and the recent spritzes of moisture have raised spirits across much of Texas and Oklahoma. Yet as bad as the past year has been, things could get even worse. La Niña events hike the odds of drought across the southern United States, and a strong La Niña was in place during the last year. Now NOAA has issued a new La Niña Advisory, heralding the return of cooler-than-normal surface waters to the eastern tropical Pacific for a second winter.

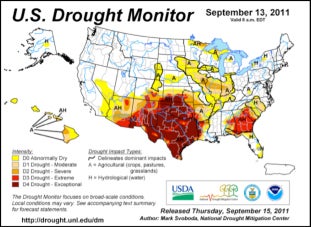

“Exceptional” drought—the most dire ranking—covered most of Texas and Oklahoma for the 13 September edition of the U.S. Drought Monitor. (Image courtesy National Drought Mitigation Center.)

Not all global computer models agree that another year of La Niña conditions is in store. In fact, several say that neutral conditions will predominate, as shown in this summary from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology and this graphic from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society. The IRI is putting the odds of La Niña and neutral conditions at about 50% each. However, cool-ocean anomalies have been intensifying over the last several weeks. Since May, NOAA’s Climate Forecast System model has sent progressively stronger signals pointing toward La Niña, and other models are now reaching similar conclusions.

Can the drought get worse? “Yes,” says Mark Svoboda of the National Drought Mitigation Center, which is based at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

Svoboda is a frequent lead author for the U.S. Drought Monitor, an invaluable weekly summary of conditions across all 50 states. The site's lead graphic tells the tale quickly: in the most recent update (reproduced below), a brick-red blob covers most of Texas and Oklahoma. This color denotes “exceptional” drought, the most severe of five categories.

Starving cattle, storm-blocking heat

Agriculture feels the pinch most directly when a drought sets in, notes Svoboda. Rangelands are now in tatters across the region, with many ranchers selling off cattle. Even if rains were to resume in earnest, Svoboda says, “those lands might not even get back to 75% of capacity for two or three years.” Also in jeopardy is winter wheat, which typically paints the countryside bright green in February while other plants lie dormant.

Yet another threat comes from “blue northers,” cold fronts that sweep from Canada into Texas with very high wind but little rain or snow. If it doesn’t rain much this fall, such wind could pose an ever-increasing threat for wildland fires on par with the Bastrop disaster.

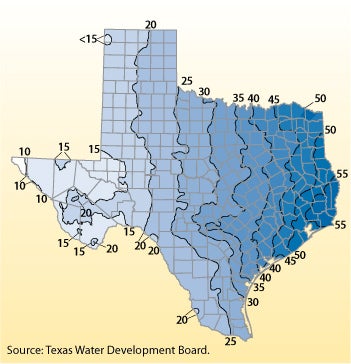

One reason why the Southern Plains can easily swing from dry to wet conditions is the strong east-west contrast in precipitation. Texas, in particular, is a high-contrast zone: the El Paso area averages less than 10 inches of moisture per year, while the far east typically gets more than 55 inches, as shown in the 1971–2000 averages above. (Image courtesy Texas Water Development Board.)

Landfalling hurricanes and tropical storms can sometimes pull the Southern Plains out of drought, but this year’s systems haven’t done the trick—they've struck either too far south or too far east. In part that’s because of the drought and heat itself: the associated domes of hot air beneath upper-level highs help steer moisture-laden systems away.

“These droughts can really feed on themselves,” says Svoboda. “Unless you get something like a tropical storm to bust that high pressure dome, what you’ve got is a source region for very hot, dry conditions and persistent drought.” The summer’s upper high has weakened, but he remains concerned that the dryness could work its way northeastward over the next few months: the odds for drought in much of Kansas and Nebraska more than double as a La Niña matures.

“My 'drought radar' really perks up in the Midwest when I see a La Niña winter, especially if it’s the second one in a row,” Svoboda explains.

Harbinger of a changing climate?

The unprecedented strength of both heat and drought across Texas has echoes in climate periods of the past as well as projections of the future. Researchers have long warned that the U.S. Southwest is prone to megadroughts—periods of dryness lasting 20 years or more that are far more intense than anything observed in the last century.

An overview by a team from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory chronicles a series of megadroughts that struck the region between 900 and 1400 A.D. Persistent cooling in the Pacific’s La Niña source region may have been a factor, they note. And megadroughts may have been a feature of southwestern climate hundreds of thousands of years ago, according to analyses of lake sediments led by Peter Fawcett (University of New Mexico) that appeared in Nature this year.

There’s also the risk that human-produced greenhouse gases will push the Southern Plains toward hotter and drier conditions on average. Warmer temperatures alone—expected to climb several degrees Fahrenheit this century, in line with global trends—will help dry the soil and intensify any droughts that do occur.

Though climate models haven’t yet pinned down future changes in regional precipitation across North America, their rough consensus is for subpolar moistening and subtropical drying—in other words, increased precipitation toward Canada and reduced precipitation toward the southern United States and Mexico.

Has global warming already played a role in the 2010–11 Texas drought? That’s the question tackled by Texas state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon (Texas A&M University) in a 9 September post on his Climate Abyss blog. He told me:

I decided to put this together because a lot of people seemed to be pointing at the Texas drought and saying, "See? Climate change!" I wanted to look at the different ways climate change might be affecting drought and see how much of what was happening fit with ongoing trends or future projections. I was also afraid some members of the public might be thinking about the drought and heat as two independent rarities rather than two interrelated aspects of the same event.

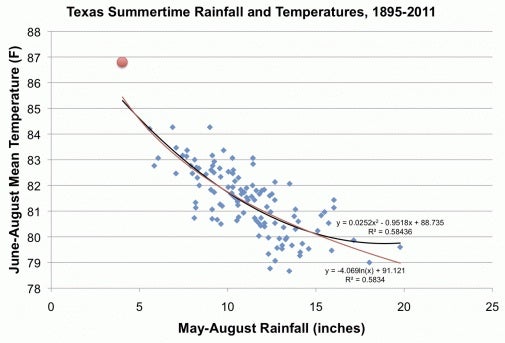

The post includes a concise summary of climate model projections, as well as Nielsen-Gammon’s own attempt to break down the excessive heat (vividly shown in the graphic below by causal factors. In a nutshell, he accounts for most of this summer’s 5.4°F (3.0°C) anomaly in Texas temperature as follows:

4.0°F: feedback from the drought

0.9°F: long-term (human-induced) climate change

0.3°F: the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)

“Note that there’s uncertainty with all those numbers, and I have only made the crudest attempts at quantifying the uncertainty,” writes Nielsen-Gammon. His calculations should thus be seen as a starting point rather than the last word.

When Texas temperatures and rainfall are plotted against each other for the last 117 years, the strong ties between heat and drought become evident—as well as the unprecedented nature of 2011 (red dot at upper left). The curves shown are best-fit second-order polynomial (black) and best-fit logarithm (red). (Graphic courtesy John Nielsen-Gammon, Climate Abyss.)

As for the causes of the drought itself, Nielsen-Gammon believes the La Niña influence was enhanced by a positive AMO, which is strongly correlated with multiyear drought across the Southern Plains (see PDF on this topic) and a negative Pacific Decadal Oscillation, which fosters La Niña-like atmospheric patterns. The AMO/PDO juxtaposition could continue for years, Nieson-Gammon notes. He believes the feedback between dry soil and hot temperature took an increasingly larger role this summer.

Given the uncertainty among climate models about future precipitation, and given the fact that Texas has become slightly wetter on average over the last century, Nielson-Gammon isn’t pinning the remarkable lack of precipitation over the last year on climate change. However, he says that the drought’s overall severity was made worse by the contribution of human-induced climate change to high temperatures and enhanced evaporation.

A lively discussion has already ensued on Climate Abyss, and peer-reviewed work will no doubt shed more light on the attribution question. Only a few studies to date have built robust arguments on what percentage of a given event can be attributed to climate change. Whatever the mix of causes, the extreme nature of the 2011–12 drought and heat reminds us that in the Southern Plains, as elsewhere, past climate performance does not guarantee future results.