Making the U.S. tornado-ready

A new approach to warnings in the wake of 2011’s fury

Feb 6, 2012 - by Staff

Feb 6, 2012 - by Staff

February 6, 2012 • Imagine your cellphone going off at midnight, with this message blinking on the screen:

Between 1:00 and 1:30 a.m., there is a 50% chance that a tornado will pass within two miles of your house.

The National Weather Service can’t offer that level of precision right now. But an NWS project gaining steam could bring us considerably closer to longer-range, probabilistic tornado warnings by the year 2020.

The tornadoes of 2011 extended into autumn: a series of twisters struck the Southern Plains on November 7, including the one pictured above near Manitou, Oklahoma. Later that day, the first November tornado in state history to be rated EF4 destroyed an Oklahoma Mesonet station (pictured below) near Tipton. (Wikimedia tornado image by Chris Spannagle; damage photo © Oklahoma Mesonet.)

Such warnings are now issued when a tornado is present or imminent, based on radar signatures and/or naked-eye reports. The name of the ten-year Warn-on-Forecast project signals a paradigm shift: the idea that some warnings could be issued via high-resolution computer models that would predict a thunderstorm’s evolution down to the fine-scale development of a twister itself.

Conveniently, it’s the most destructive and deadly tornadoes that could lend themselves best to the Warn-on-Forecast approach, because they emerge from the kind of well-organized, long-lived supercell storms that models are increasingly skilled at depicting. Yet it’s far from clear how best to turn the coming wealth of data into words, numbers, and images that will grab the eyes and ears of the public and motivate people to act.

“Warn-on-Forecast is the way to a safer future if we can figure out how to implement it,” says Tim Spangler, director of UCP’s COMET program.

Spangler was one of nearly 200 professionals who spent three days exploring the perils and potential of new warning approaches for severe weather on December 13–15 at a meeting in Norman, Oklahoma, coordinated by UCP’s Joint Office for Science Support. It was the first in a series of “national conversations” being conducted by NOAA as part of Weather-Ready Nation, an initiative launched last summer in the midst of 2011’s varied weather disasters. These included the deadliest single U.S. tornado in more than 60 years (the Joplin, Missouri, twister on May 22 that killed at least 158 people) and the most prolific one-day tornado swarm ever recorded (the 2011 Super Outbreak of April 27, which produced around 200 tornadoes in 24 hours).

“If there is one word to describe Weather-Ready Nation, I would say it is a mindset,” said NOAA administrator Jane Lubchenco in a message to workshop participants. “Do people hear and understand the information we think we’re providing? And do they respond in ways that protect themselves and their property, whenever possible?”

The December workshop drew an uncommonly wide range of experts. A large contingent of social scientists was on hand, along with meteorology researchers, communication specialists, emergency managers, private weather forecasters, and others. “It was the first meeting that I’ve attended where physical and social scientists were on equal footing,” said NCAR director Roger Wakimoto, a longtime tornado researcher. “Indeed, the social scientists dominated the discussion at several of the sessions I attended. This was both refreshing and important if we want to achieve a weather-ready nation.”

The eleven themes emerging from the meeting were equally wide-ranging (see box). “There were many good ideas in each category,” said John Ferree, severe storms services leader for the NWS and one of the workshop organizers.

Scenes from the workshop: (top) a journalist interviews John “Jack” Hayes, director of the National Weather Service; (middle) Russell Washington (Federal Emergency Management Agency) addresses a breakout group; (bottom) physical and social scientists joined forces with public safety specialists and others for plenaries and breakouts. (Photos by James Murnan, NOAA Weather Partners.)

Just as 2005’s Hurricane Katrina was well forecast yet catastrophically deadly, the tornadoes of 2011 killed hundreds despite the NWS’s best efforts. Everyone in the path of the most violent twisters had been alerted via a tornado watch as much as six hours in advance. And in each case, warnings were issued as much as 30 minutes or more ahead of the tornado’s arrival. What went wrong?

Bad luck was partially to blame. Last year’s tornadoes were exceptionally strong and numerous, and many happened to strike populated areas. However, post-storm surveys confirmed a longstanding finding: many people don’t take cover right away upon hearing a tornado warning. Having seen other watches and warnings come and go without incident, they may choose to wait until the alert is confirmed in some other way—the blast of a siren, a call from a neighbor, or a glimpse of the tornado itself. An NWS assessment found that many residents of Joplin postponed action until the massive tornado and its 200-mph winds were only moments away.

Many of the ideas discussed in Norman involved using GPS-based technology to make warnings as specific and coordinated as possible, thus reducing the false-alarm impression that lulls so many into danger. The NWS already uses an automated system that extrapolates the motion of high-risk storms to give an initial estimate of the area at risk. This area is then edited by the warning forecaster and disseminated as a polygon that identifies the locations in its path. These polygons, often shown on weathercasts, are converted into the text-based, county-oriented warning statements read by radio hosts and scrolled across TV screens.

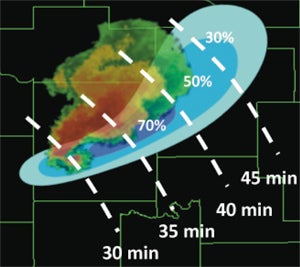

Instead of this “on or off” approach (you’re either in a warning or you’re not), the Warn-on-Forecast method would assign probabilities, with the greatest risk toward the center of the area and decreasing probabilities outward from the center. These would be calculated with the help of storm-resolving computer models—some with resolutions of 250 meters (810 feet) or less—that will soon be practical for everyday use. Such models would also assimilate up-to-the-minute data from radar and other sources.

In the conceptual model of Warn-on-Forecast, a tornado warning might include probabilities (shaded) that a tornadic signature on radar will affect a particular area, as well as the timing of greatest risk (dashed lines). (Image courtesy Warn-on-Forecast.)

Tornado science may be outrunning society, though. Even today’s less-complex warning messages aren’t getting to the public in a consistent way. Municipal sirens are sounded by city staff based on funnel-cloud sightings and other cues that may not match NWS warnings. An increasing fraction of the public doesn’t speak English. And the poorest Americans, those most likely to live in mobile homes and other high-risk structures, are also least likely to carry the smartphones that could be the favored warning delivery devices of tomorrow. As one workshop participant put it, “We can’t pass a law that requires everybody to carry a smartphone.”

Among the many ideas floated for addressing these and related problems:

“For me, a large outcome of the workshop was the recognition that in order to save lives, many of the primary actions needed are outside the purview of the weather community,” said economist Jeff Lazo, head of NCAR’s Societal Impacts Program. SIP’s Julie Demuth agrees: “I’m optimistic that we may be seeing the beginnings of a true paradigm shift.”

The dialogue launched in Norman will continue at a town hall meeting in January at the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society (AMS), where participants will be briefed on key priorities identified at the workshop. NOAA will also hold additional symposia, town halls, and other events in 2012 under the Weather-Ready Nation umbrella.

“Social science is not a quick fix, and our work takes time and other resources,” noted Heather Lazrus, an environmental anthropologist now on a postdoctoral appointment at NCAR. “We need to understand better how people communicate, understand, and evaluate risks and how they make decisions that may keep them safe.” Lazrus and others, including AMS senior policy fellow William Hooke, emphasized the need to build on existing social-science efforts such as SIP. “We need to strengthen the think tanks we’ve got,” he said.

NCAR’s Morris Weisman, who has studied tornado dynamics since the late 1970s, came away from the December workshop encouraged. “We’ve made amazing strides in the science of tornado forecasting and warning. But even if reliable one-to-two-hour forecasts become a reality, it’s not clear how society can or should respond to such information. This meeting was by far the most comprehensive and constructive attempt I’ve experienced at highlighting and promoting such issues.”

Video from plenary sessions is available on the workshop’s website.

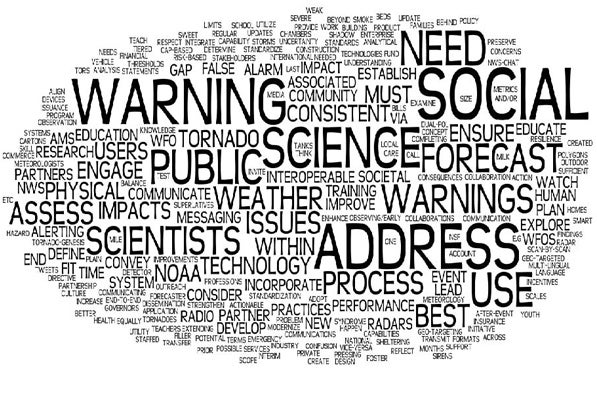

This “word cloud” was created by Greg Carbin, warning coordination meteorologist at the Storm Prediction Center, to summarize key themes from the closing break-out sessions of the Weather-Ready Nation meeting held in December 2011. (Image courtesy Greg Carbin.)