Rocky Mountain dry

A snow-starved March puts residents on edge

Apr 3, 2012 - by Staff

Apr 3, 2012 - by Staff

Bob Henson | April 3, 2012 • If snow is the lifeblood of Colorado’s economy and ecology, then my home state is ready for a transfusion. March is normally the snowiest month of the year for much of the state, but March 2012 will go down as an epic snow fail.

Tallgrass struggle to survive on parched land in eastern Colorado in this file photo. (©UCAR. This image is freely available for media & nonprofit use.* Click for high resolution.)

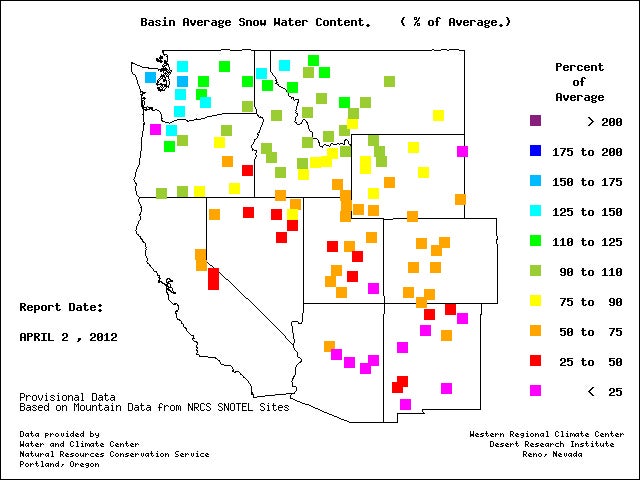

It’s been a similar story at high elevations throughout most of the nation—except for the coastal mountains from Oregon to Alaska, where frequent storms have dropped a bountiful snowpack. Anchorage has seen its second snowiest winter on record, with only 3.2” more inches needed to nab first place.

Meanwhile, conditions across the Rockies have gone downhill fast, with a number of ski resorts planning to trim hours or shut down earlier than scheduled. In the east, at Vermont’s venerable Sugarbush ski area, temperatures shot above 65°F before the first day of spring. “It is really sad to see what this hot sun is doing to our slopes and all the others in the Northeast,” blogged Sugarbush president and owner Win Smith.

March statistics for the contiguous United States, soon to be compiled, may show it to be one of the most exceptional months in American weather history. In Des Moines, Iowa, for example, no other month in any year has ever vaulted so far above average. Here in Colorado, it was not only mild but also extremely dry. The March 27 edition of the U.S. Drought Monitor shows virtually the entire state at some level of drought.

For the first time in more than a century of weather records, both Denver and Boulder saw no measurable snow in March. Only 0.03 inches of moisture fell in Denver and just 0.01 in Boulder. In both cases, those are the lowest totals ever seen in March. You’d have to go back to February 1992 to find a drier month in Boulder. A slow-moving storm finally gave the Denver area its first measurable snow in six weeks on April 3, although the amounts were generally modest.

A light snow on April 3, 2012, coats a tree in Boulder whose buds and leaves got an early start in the March warmth. Although the month also saw record dryness, trees have taken advantage of deeper moisture from heavy February snow. (©UCAR. Photo by Carlye Calvin. This image is freely available for media & nonprofit use.*)

As for warmth, the only March that topped this year across the two cities was in 1910. The icing (as it were) on the 2012 cake came at month’s end, as both Denver and Boulder soared above 80°F (27°C) on both Saturday, March 31, and Sunday, April 1. The month’s unprecedented blend of warmth and dryness helped stoke the Lower North Fork fire southwest of Denver on March 26, which killed three residents and destroyed dozens of homes.

Across the central Rockies, mildness and dryness have taken their toll on the region’s snow cover. Looking at today’s stats, snowpack moisture in Colorado is a paltry 51% of normal at the measurement sites in the western states’ SNOTEL network. The percentages aren’t much better to the west (51% in Utah, 53% in California) and they’re far worse to the south (25% in New Mexico, 15% in Arizona). The saving grace for water users is that reservoirs are still nearly full after last year’s wet winter, but continued dryness could eventually take its toll.

The oddly warm temperatures helped torque the timing of snowfall across the nation in some interesting ways. At New York’s Central Park, the total snowfall was on the low side—only 7.4 inches (18.8 centimeters) as of April 2—but what’s more notable is that the winter’s second biggest snow (2.9 inches) fell on October 29. It was the first time the city had ever gotten as much as an inch during October.

Boulder had its own memorable event in midwinter, when cold temperatures normally prevail and snowfall tends to be lighter. On February 3–4, the city was pummeled by 22.7 inches. It was the biggest-ever February snowfall for Boulder and helped lead to the snowiest February on record, followed by the least snowy March on record.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that an area renowned for precipitation extremes could pull off such a back-to-back feat. In fact, a similar thing happened—but in reverse—in 1970. That year saw Boulder’s least snowy February (tied with several other years, with only a trace measured), followed by its snowiest March (56.7 inches). Both records remain on the books, notes UCAR’s Matthew Kelsch, who maintains the city’s cooperative weather station along with NOAA’s John Brown.

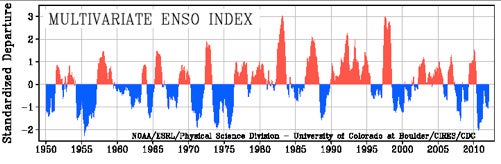

Klaus Wolter, a scientist at NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, sees a fork in the road for April. Wolter is the creator of a widely used index for the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which includes both El Niño and its counterpart, La Niña.

The period since 1950 has seen a number of mulityear stretches dominated by either El Niño (red peaks) or La Niña (blue peaks), as shown in this graph of the Multivariate ENSO Index devised by NOAA's Klaus Wolter. (Image courtesy NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory.)

Right now the tropical Pacific Ocean is winding up its second year of La Niña, which is strongly correlated with dry conditions in March across the southwestern states. But April could swing either way, according to Wolter. “If you look at the ten driest Marches for the state of Colorado, the subsequent April has always ended up in either the driest third or the top 15%,” he says.

Wolter is also looking ahead to 2012–13, where history is clashing with model projections. ENSO events typically grow during the northern fall and wane in the northern spring. The official model-based probabilistic forecast of ENSO, issued monthly by NOAA and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, shows the tropical Pacific easing into neutral conditions by mid-2012, per usual. By late 2012, it gives a one-in-four chance that La Niña will return for a third year. The odds are higher for the arrival of an El Niño (about 35%) or for neutral conditions (almost 40%).

If history is any guide, a neutral 2012–13 may not be in the cards. Looking at ENSO data extending back to 1900, Wolter found 10 examples of back-to-back La Niña years. In 6 of those cases, an El Niño followed; in the other 4, La Niña returned. The latter is an especially worrisome possibility, notes the Colorado Department of Water Resources in a late-March report.

“Three-year La Niña events have been associated with some of the driest periods on record for Colorado,” the report noted.

The amount of water held in snowpack on April 2, 2012, was above average for this time of year in parts of the Pacific Northwest but well below average across much of the central and southern Rockies. (Image courtesy Western Regional Climate Center.)