Four surprises from Sandy

Things hurricanes don’t usually do

Oct 29, 2012 - by Staff

Oct 29, 2012 - by Staff

Bob Henson | October 29, 2012 • Hurricane Sandy is on track to carve its way into weather annals. It’s one of the largest and strongest hurricanes ever to approach the northeast U.S. coast, with tropical storm force winds (39 mph sustained) spanning more than 1,000 miles. And the center is projected to strike the New Jersey coast from the east—a scenario never observed since weather records began in the late 1880s.

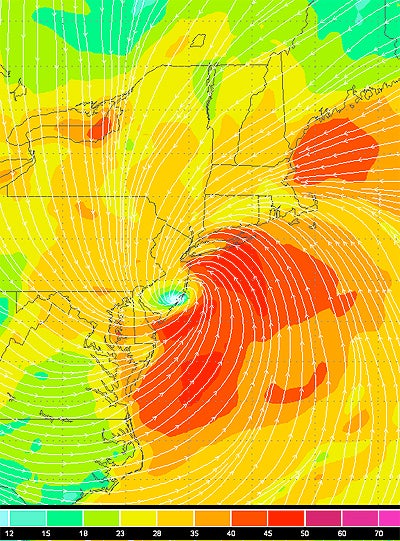

Sandy’s immense circulation is evident in this forecast of winds in the NAM model, issued at 1200 UTC Monday and valid for 0000 UTC Tuesday (8:00 p.m. EDT Monday, about an hour before high tide in New York City). Along with the sustained winds of 40-50 knots (46–58 mph) near the storm, pockets of strong wind are projected off the Massachusetts coast and over Lake Ontario. (Image courtesy Wundermap.)

There will no doubt be devastating and deadly effects from this extremely rare and dangerous scenario, including life-threatening storm surge in the New York area (see below). With Sandy covering such a large area, there are also bound to be surprises, including some impacts one doesn’t expect in a hurricane. Here are four very unusual aspects of Sandy.

Huge waves and wind in upstate New York. Sandy’s unusual path and vast circulation will push powerful north winds across the Great Lakes, producing wind gusts as high as 50-60 mph and waves of 20 feet or more from Chicago eastward.

In western New York, such strong, sustained winds from the north are extremely rare, according to the National Weather Service office in Buffalo. Since tree roots there have grown in response to the more typical west and southwest winds, “[we] expect more wind damage with this event than we typically see with wind gusts in the 50-65 mph range,” said the Buffalo NWS office in a statement this morning. The north-south orientation of the famed Finger Lakes may help channel and concentrate the north winds even further.

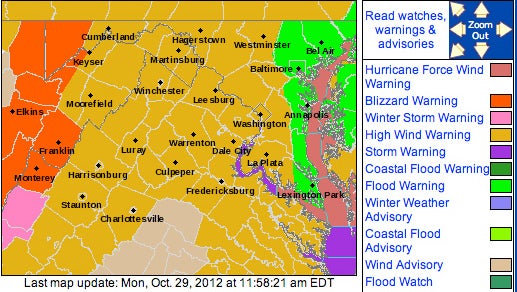

Blizzard and hurricane wind warnings in the same state. As Sandy moves west and gradually transforms into a hybrid storm, it’ll bring a tropical airmass into New England while pulling cold air around its west and south side. A telling sign of this contrast: while the Maryland shore is dealing with damage from high wind and waves, far western Maryland is under a blizzard warning. At some of the higher elevations of West Virginia and neighboring states, snow will likely be measured in feet.

In Maryland, current NWS warnings run the gamut from flood and hurricane-force wind to blizzard. (Image courtesy NWS, Baltimore/Washington.)

U.S. snowfall related to a transitioning hurricane is rare, but it’s happened before—most spectacularly in the Great Storm of 1804, when a mid-October hurricane dumped snows as deep as 2 to 4 feet in New England while moving along the northeast coast and becoming post-tropical. Another October storm, Hurricane Ginny, brought more than a foot of snow to parts of Maine in 1963.

High water in and near New York City. One of the most worrisome aspects of Sandy is its potential for record-breaking floods in New York Harbor and in Long Island Sound, the narrow channel of water between New England and Long Island. Since most hurricanes and nor’easters are moving from southwest to northeast, they seldom have a chance to funnel water from east to west across Long Island Sound for long periods. Sandy’s westward hook will push high waves and water into the Sound, which progressively narrows as it approaches New York City.

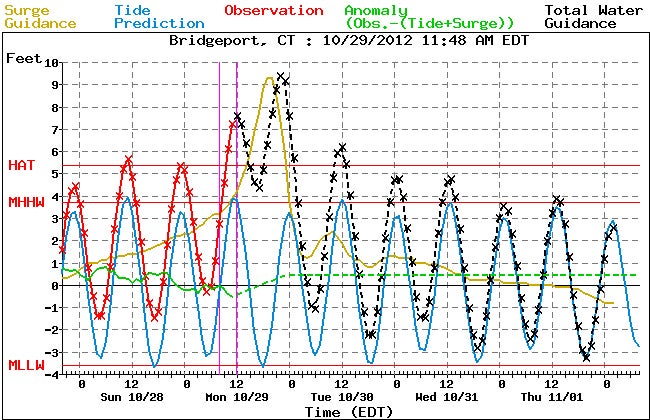

The critical factor will be timing. With today’s full moon, high tide (apart from the storm) will be up to 8 feet higher than low tide, so the impacts of the predicted 6–11 feet surge could go up or down by more than 50% depending on exactly when the surge peaks. Extremely dangerous surge is also possible along many other parts of the New York coastline, as warned by the New York NWS office.

Quick clearing? Not likely. Sandy is being deflected by an enormous high-pressure bubble east of Canada and pulled into a midlatitude storm digging into the eastern United States. After it comes onshore tonight, Sandy will slow down and spin in or near Pennsylvania for a day or more. It’ll weaken substantially in the few hours after landfall, but chilly winds, clouds, and showers may linger through Wednesday in many parts of the Northeast—not exactly the quick transition to sunshine and warmth that often occurs in the wake of a hurricane. Such weather may cast a gloomy pall on the damage surveys and massive cleanup destined to unfold in Sandy’s wake.

Guidance from NOAA’s Extratropical Surge and Tide Operational Forecast System (ESTOFS) indicates how things will unfold if the peak storm surge (tan line) were to strike in between two high tides (blue line). The dashed black line indicates the forecast for peak water level above mean sea level (the “0” line in this graph). If the peak of the surge coincides with the evening high tide, the peak water level would be higher than shown in the dashed black line. Water level heights are also sometimes compared to mean lower low water (MLLW, the lowest red line). Note: These projections are purely computer-generated and not intended for public decision making; please consult local NWS offices for officlal watches and warnings. (Image courtesy NWS Meteorological Development Laboratory.)