When a good air mass goes bad

While the East freezes, the West coughs through stagnant cold

Jan 24, 2013 - by Staff

Jan 24, 2013 - by Staff

Bob Henson • January 24, 2013 | Much of the United States has felt winter’s bite this week, but for two distinctly different reasons. In the Midwest and East, a series of fresh but frigid air masses sweeping in from Canada has sent temperatures to their lowest levels in several years (see "Meanwhile, back east," below). On the other side of the nation, much of the Great Basin has been mired in a weeks-long spell of stagnant cold that’s led to dangerously polluted air and a rare, hazardous bout of freezing rain in the Salt Lake City area.

Cold air masses that trap pollution are a perennial aspect of winter in Salt Lake City. In this view looking to the west on January 6, 2011, the city's downtown is cloaked in smog, while peaks of the Wasatch Range are visible in the distance. Observations collected in the winter of 2010–11 have been analyzed by researchers in the Persistent Cold-Air Pool Study. (Creative Commons photo by Tim Brown, Infinite World.)

It all started with something beautiful: a midwinter snowstorm that coated much of the Intermountain West on January 9 and 10. But that blanket of white, so coveted by skiers, has helped create an ongoing nightmare for people in many towns and cities across the Great Basin, especially Salt Lake City.

Like a giant bowl, the vast area between the Rockies and the Sierras is well designed to trap a cold air mass and foster the development of fog, smog, and murk for days on end. A fresh snow cover often sets the stage by maximizing radiative cooling so that temperatures plunge at night. In most places, sunshine and the natural parade of weather would lead to a warmup within several days. But when mild Pacific air is flowing atop trapped, denser surface air, the cold below may be too stable to “mix out” with the air aloft.

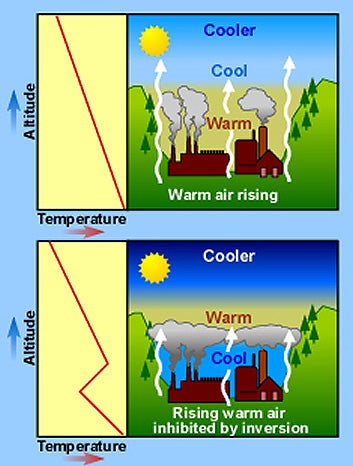

In the most extreme cases, there’s a strong inversion above the cold, polluted air near the surface. Normally, air gets progressively colder as you go up through the atmosphere, but sometimes the temperature in a shallow layer actually increases with height (thus inverting the usual temperature-altitude relationship). And this week has seen one doozy of an inversion over Salt Lake City.

On Wednesday morning, January 23, it was a smoggy 4°F (–15ºC) at the SLC airport—but if you were to ascend about half a mile that morning, or head over to the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, you’d have found sparkling sunshine and temperatures around 45°F (7°C).

In a well-mixed atmosphere (top), temperature drops consistently with height, and pollutants near the surface are dispersed by rising plumes of warm air. When a shallow, stable inversion is present (red line in bottom graph), polluted air is trapped below the inversion. (Graphic courtesy Windows to the Universe.)

It’s been dubbed “the mother of all inversions” by Jim Steenburgh, a University of Utah professor and an expert on Western meteorology. Steenburgh runs the Wasatch Weather Weenies blog, where he’s been dolefully documenting the unrelenting cold as well as the buildup of dangerous air pollution near the ground.

The grim reportage is leavened by plenty of cool science and touches of humor. (One entry, which shows the smoggy inversion as viewed from above, is titled, simply, “Ick.”)

It can take weeks before an upper-level trough arrives that’s strong enough to stir the Great Basin’s air and break up the inversion. Ironically, air quality is often worst just before the fresh air breaks through. As the inversion begins to erode, pollutants are trapped in an ever-more-confined space.

Particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5) are especially problematic for human health, as they can pass into the respiratory system more easily than larger particles. In North Provo, Utah, about 40 miles south of Salt Lake City, the total mass of airborne PM2.5 particles was 127.8 micrograms per cubic meters on January 23. That’s almost four times the National Ambient Air Quality Standard, notes Steenburgh.

“These numbers lag Beijing by quite a bit, but they are still quite bad,” he adds. On Wednesday, more than 100 Utah physicians urged state legislators to declare a health emergency.

From a mild, sunny vantage point above Little Cottonwood Canyon in the foothills east of Salt Lake City, the smoggy inversion enveloping the city to the west on January 19, 2013, was clearly visible. The temperature at this point, at about 6,000 feet (1,830 meters) above sea level, was roughly 18°F (10°C) warmer than at the lower end of the canyon. (Photo courtesy Jim Steenburgh, University of Utah.)

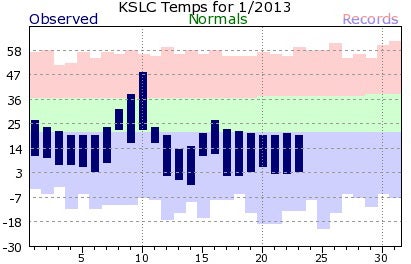

Some relief may be on the way as a strong trough approaches this weekend. Current forecasts bring the Salt Lake area and much of the interior West above freezing over the next few days. The thaw will arrive none too soon. From January 1 to 23, Salt Lake City’s average temperature (incorporating both highs and lows) was only 15.9°F (–8.9°C). Though that number is bound to rise before January ends, it’ll still be one of the city’s coldest months on record.

The coup de grace occurred this morning (January 24), as the Salt Lake area was coated with a rare glaze of rain falling from warmer air aloft into 20°F surface air, closing the city’s airport and causing hundreds of accidents. “Freeways are a mess of bumper cars,” reports former NCAR meteorologist Ed Zipser, who’s experiencing his first such event since joining the Utah faculty 14 years ago.

This is only the tenth freezing rain in Salt Lake City in the last 72 years, and temperatures in all other events were 26°F or warmer, says Trevor Alcott (National Weather Service Western Region Headquarters). The city's prolonged, deep chill left highways and other surfaces primed for the rain to freeze on them.

“Nearly every winter in New England offers an ice storm that could put this event to shame,” says Alcott, “but in the Intermountain West, this is a very unusual scenario.”

Why is the Salt Lake Valley the epicenter of the Great Basin’s gunkiest air? Of course, it gets a head start simply by being the largest metropolitan area in the Intermountain West, but there’s more to the story.

Temperatures have trended well below average in Salt Lake City through most of January 2013, with highs on many days failing to get even as warm as typical morning lows. In this graph, days of the month appear along the bottom axis. Temperature readings (left axis) are shown in degrees F. The dark blue bars indicate each day’s high and low compared to the average daily range (green) and the records for each date (top of the salmon bars and bottom of the purple bars). (Image courtesy National Weather Service, Salt Lake City.)

“The Salt Lake Valley has some of the worst wintertime pollution episodes in the West due to the combination of its increasing population and urbanization, as well as its geometry, with the valley sandwiched between mountain ranges to the west and east,” says John Horel (University of Utah).

That geometry leads to interesting and complex meteorology, as explored recently by Horel and fellow scientists analyzing a winter’s worth of research observations. The Persistent Cold-Air Pool Study took place from December 2010 to early February 2011. PCAPS cast a dense observational net over the Salt Lake Valley in order to better understand how the region’s notorious inversions form, persist, and finally break up.

A team from NCAR helped set up and run the equipment, which included more than two dozen observing towers, radiation sensors, laser ceilometers, and a portable system for launching radiosondes (weather balloons).

In contrast to the smogginess of the Great Basin’s recent cold, the northeastern half of the nation has been swept by a steady stream of northwesterly winds at upper levels. These are bringing down reinforcing shots of bitter but clean air from Canada, a setup that tends to keep things fairly breezy and scour out any major buildups of pollution.

The eastern cold wave hasn’t been especially brutal by historical standards. But given the startling warmth of the last couple of winters, there’s definitely an edge to the chill—particularly at New Hampshire’s famed Mount Washington Observatory. Its observer blog and three-day weather history show temperatures lodged below –20°F (–29°C) over the last couple of days, with gale-force winds pushing wind chills as low as –86°F (–66°C).

By and large, the daytime temperatures in this cold wave have been more impressive than the nighttime readings. On Tuesday, January 22, only a handful of stations in the Midwest set or tied record lows. However, more than 100 set or tied record low maxes—i.e., their high temperatures for the day were lower than on any other January 22 in their observing histories. The graphic above, from NOAA's National Climatic Data Center, shows all record low maxes for January 1–23, with the western and eastern foci of cold evident. Check out NCDC's U.S. Records site for an enlarged version.

Washington, D.C., is expected to stay below the freezing mark for up to six days, the longest such stretch in almost a decade.

Minneapolis passed its own noteworthy benchmark on Monday, January 21, the first day since 2009 that the airport stayed below 0°F. That’s the longest the city has gone without a below-zero day since Twin Cities observations began in 1873.

The project successfully documented 10 multiday cold-air pools, which don’t necessarily have to be inversions in order to persist and trap pollution. Results have been shared on the project’s informative website and in a number of presentations and papers, including a full report in the January 2013 issue of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Horel is one of the three principal investigators for PCAPS. He and colleagues are undaunted by what I often call the Field Project Effect: when a classic example of a phenomenon you’re studying occurs after you’ve ended a field study.

“The two really bad air pollution events we’ve had this winter in Salt Lake City were what we expected would happen during the 2010–11 winter: big snowstorms followed by ridging aloft and building air pollution as a result,” says Horel. However, he adds, “we had much milder conditions during PCAPS and more cloud cover, and we still had really bad air pollution episodes then.”

Horel and fellow PIs David Whiteman (UU) and Sharon Zhang (Michigan State University) have been simulating the PCAPS cases using numerical models and learning a good deal. “How the events finally ‘mix out’ has been a particular focus, as it involves flow interacting with the lower terrain to the south of the Salt Lake Valley and surprisingly large impacts from the Great Salt Lake to the north.”

The observing continues this winter, as two new ceilometers of the type deployed for PCAPS are now being used to study the anatomy of low-level particle buildups in the Salt Lake Valley as well as very high ozone levels in the Uintah Basin to the east.

Though the science of inversions keeps the Utah faculty intrigued, they’re also human beings who crave fresh air as much as anyone. “As fascinating as all this is meteorologically," says Steenburg, "I’m looking forward to this episode being over.”