The eyes of winter

What’s causing those swirling, circular gaps in storm clouds off the U.S. coasts?

Feb 22, 2013 - by Staff

Feb 22, 2013 - by Staff

Bob Henson • February 22, 2013 | It’s been quite a month for cloud appreciators. Satellite images have revealed at least three dramatic eye-like features not far off the U.S. Atlantic and Pacific coasts over the last several weeks. While these can look startlingly like the eyes of hurricanes, they’re not quite the same thing.

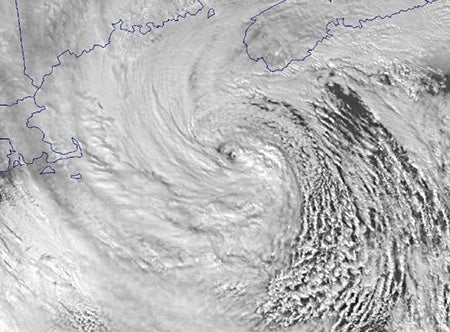

Two of these pseudo-eyes formed within major winter storms (extratropical cyclones) centered east of New England. One of these systems—dubbed Nemo by the Weather Channel—pummeled the Northeast with up to 40 inches of snow on February 8–9.

A small eye-like feature appears amid the intense circulation around this low-pressure center. The storm brought extremely heavy snowfall to the northeast U.S. on February 8–9. (Image courtesy SSEC/CIMSS.)

As the blizzard wound down in New England on the 9th, the still-powerful center of low pressure, well offshore, developed a tiny eye-like feature (see photo).

This isn’t uncommon in the strongest nor’easters. Although extratropical cyclones typically have cold cores, a small pocket of warm air can be pulled from the warm side of the circulation and pinched off at the center of the cyclone. It’s one aspect of the Shapiro-Keyser process, outlined by researchers Mel Shapiro (NCAR) and Daniel Keyser (University of Albany, State University of New York). This process also factored into Superstorm Sandy as it neared landfall; see my writeup from November 2.

Eye-like features have been spotted in nor’easters for decades. In a 1981 paper for Monthly Weather Review (PDF), Lance Bosart (University at Albany) discussed the presence of such a feature in the President’s Day snowstorm of 1979. And sharp-eyed Syracuse meteorologist/blogger Dave Eichorn noted the visual similarity between this month’s northeast blizzard and its colossal predecessor, the Blizzard of 1978, which sported its own eye-like center.

In a well-developed hurricane, air rises rapidly through a tight ring of convection (showers and thunderstorms). But these furious updrafts are counterbalanced by air that’s being forced downward, both outside the storm and at its center. Air must rise to generate clouds and precipitation, so the subsidence in the middle of the storm tends to produce an eye with clear skies and relatively calm conditions—all surrounded by powerful thunderstorms that can tower up to 8 miles (13 km) or more.

Some of the same circulation patterns may be at work in extratropical cyclones that produce eye-like features. But these cyclones aren’t as symmetric as hurricanes, and much of their rain and snow is produced by stratus clouds that are significantly more shallow than thunderstorms. Thus, the eye-like components in extratropical cyclones aren’t usually as clear-cut as in a hurricane, and they seldom last long.

“I would call these ‘false eyes,’ ” says David Nolan (University of Miami). “A real hurricane eye has deep convection and also dynamically forced sinking down the middle.”

Other types of cold-season weather can produce even more spectacular “eyes.” Polar lows—often informally called Arctic hurricanes—are a common feature of high-latitude winter, and they’re indeed like cousins of hurricanes in some ways. Despite the chilly environment overall, the warmest air in polar lows is at the center, in contrast to the cold-core nature of most extratropical cyclones. Winds in a polar low can exceed gale force, and their eye-like features can be quite prominent. The Polar Lows website (spotlighting “the coolest weather on the planet”) has plenty of examples.

Despite its eerie visual similarity to a hurricane, this coastal eddy brought winds of little more than 10 mph as it approached the California coast near San Diego on February 17. (Aqua/MODIS image courtesy SSEC/CIMSS.)

Atmospheric eddies off the coast of southern California can also produce distinctly clear centers that resemble hurricane eyes. One dramatic example occurred last weekend west of San Diego (see photo).

The islands off southern California, such as Catalina and San Clemente, help produce many of these coastal eddies. Often they occur within vast fields of marine stratocumulus clouds.

Sometimes these eddies are individual, but when strong winds strike an island, the flow can create pairs of oppositely rotating vortices that move downstream. The result is called a von Karman vortex street. These patterns are entrancing enough that an entire website is devoted to images, explanations, and predictions of von Karman vortex streets off Guadalupe Island.

How could a modest coastal eddy produce a feature as cloud-free and symmetric as the eye of a Category 5 hurricane? “I must admit the clearness is remarkable,” says Nolan. “It may be possible that a portion of the updraft is recirculating back to the center and descending, like in a hurricane. Perhaps it only takes a tiny amount of descent to clear out the shallow stratocumulus.”

As Scott Bachmeier (CIMSS Satellite Blog) notes, eddy features off the coast of Southern California are not uncommon. However, the case pictured at right caught Bachmeier’s eye, as it were.

“I’ve never seen an eddy there take on such a well-defined eye-like feature,” he told me.

We can be grateful that this eddy brought only light breezes to southern California. If nothing else, that spared us from the headline, “False Eye Lashes Coast.” (Hat tip to climate scientist and fellow pun lover Joe Barsugli.)