It was so cold! (How cold was it?)

Reviewing the winter of our disbelief

Mar 4, 2014 - by Staff

Mar 4, 2014 - by Staff

Bob Henson • March 5, 2014 | Even as frigid air kept parts of the Midwest and Northeast in a headlock, the remarkable meteorological winter of 2013–14 ended on Friday. That’s based on how weatherpeople define the season in the Northern Hemisphere: December through February, which are the three coldest months of the year in most mid- and high-latitude areas. So perhaps now is a good time to start putting this memorable period in our rear-view mirror. (We'll have to wait till March 20 for the Northern Hemisphere Spring Equinox.)

A snowplow rumbles through Nashua, New Hampshire, during a major New England snowstorm on February 5, 2014. (Photo by Mark Buckawacki, Wikimedia Commons.)

One common question is whether this winter was a harbinger of more cold winters to come for parts of the country, or if it was simply an outlier at a time of largely warming winters. Another question of keen interest to meteorologists: How this winter ranked historically. As cold as it seemed, the December-January period failed to crack the 25 most frigid such periods for the contiguous United States in more than a century of recordkeeping.

We won’t know exactly where this winter’s U.S. temperatures rank until NOAA releases those numbers next Thursday, March 13. But we’ll do some preliminary number-crunching in the second half of this post to begin assessing the nature of these last three extraordinary months.

Update – March 13: According to NOAA, the meteorological winter of 2013–14 (Dec.-Feb.) was only the 34th coldest out of the last 119 winters on record for the contiguous United States.

Even though climate change would be expected to produce more moderate winters over time, there have been several notably cold, snowy winters across North America and Eurasia over the last decade. Much of the slowdown in global atmospheric warming over that time appears to be due to these chilly northern-midlatitude winters. Some journalists and scientists are asking whether the future holds more vicious winters in store for the eastern U.S.

![]()

The winter of 2013–14 in a nutshell. Multiple surges of frigid air sweep across eastern North America during January–February 2014, as shown in this visualization from NCAR’s Computational & Information Systems Laboratory. The maps depict surface air temperatures, which are measured at a height of 2 meters (about 6 feet) above ground level. The flow of cold air into the eastern United States was facilitated by the upper-level “polar vortex,” not shown, which shifted from its average location near the Arctic into lower latitudes of eastern North America several times during the winter of 2013–14. These hour-by-hour images are based on data generated by the NOAA Climate Forecast System model and visualized using NCAR Command Language software. The model was updated with observed data every six hours. Click on the "Full screen" brackets icon at lower right in the video to enlarge. (@UCAR. This image is freely available for media & nonprofit use.)

Global climate models don’t tend to generate any dramatic increase in the kind of polar-vortex displacement that brought cold wave after cold wave to the central and eastern U.S. this winter. Meanwhile, Jennifer Francis (Rutgers University) and colleagues have been analyzing recent trends in the nature of the jet stream. They’ve presented evidence that large-scale ridges and troughs in the upper atmosphere are becoming more amplified and moving more slowly. This would presumably lead to more persistence in whatever extreme weather might be occurring, as Francis and Stephen Vavrus (University of Wisconsin–Madison) argued in a high-profile 2012 study.

Francis hypothesizes that these events could be a result of the dramatic loss of Arctic sea ice in the last 10 to 15 years. She presented the concept in congressional testimony last July. “As the oceans continue to absorb additional heat trapped by ever-accumulating greenhouse gases, and as the Arctic continues to warm faster than the rest of the globe, we can only expect to see more weather-related adverse impacts,” Francis said.

Francis’s methodology has been vigorously critiqued by other researchers, including Elizabeth Barnes (Colorado State University). Yet her concepts have been widely cited as an explanation for this winter’s unusual patterns. A group of eminent atmospheric researchers, including NCAR's Kevin Trenberth, published a letter in the journal Science on Feburary 14 urging caution in attributing the winter of 2013–14 to Arctic-ice effects.

“The research linking summertime Arctic sea ice with wintertime climate over temperate latitudes deserves a fair hearing. But to make it the centerpiece of the public discourse on global warming is inappropriate and a distraction,” wrote the authors. “Even in a warming climate, we could experience an extraordinary run of cold winters, but harsher winters in future decades are not among the most likely nor the most serious consequences of global warming.”

A fresh primer on the work led by Francis, and the debate swirling around it, is this article by science journalist Chris Mooney. It features a 40-minute podcast dialogue between Francis and Trenberth. In contrast to red-herring debates over whether greenhouse emissions can have much of an effect on climate at all, this one offers a taste of atmospheric science in action, wrestling with a question that has nuance and mystery as well as huge implications.

A more immediate question, and one that should be settled next week, is whether this winter will rank among the coldest in U.S. history.

It was a far different winter if you lived in Los Angeles as opposed to New York, or Seattle compared to Chicago. The unusual persistence of jet-stream patterns across the Northern Hemisphere meant that the now-infamous polar vortex made repeated incursions into the Midwest and Northeast. Meanwhile, the far U.S. West had persistently mild weather, with many record highs in the 70s and 80s across California and the warmest winter on record in Las Vegas and Tuscon. The animation above, produced by NCAR’s Computational & Information Systems Laboratory, shows just how lopsided North American temperature patterns have been.

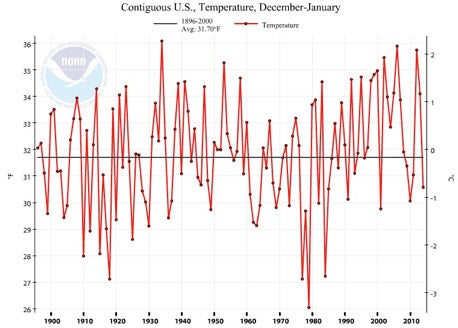

When it’s all said and done and the contiguous 48 states are averaged out, this winter may not even make the list of top 10 coldest. For December and January combined, it was the nation’s 33rd chilliest in 119 years of record keeping (see graph).

The mean temperature in the contiguous U.S. for December–January 2013–14 (the dot at the far right end of the graph) was almost 1°C (1.8°F) below the century-scale average. (Image courtesy Climate at a Glance, NOAA National Climatic Data Center.)

Of course, the national average means nothing if you live in a place like Ironwood, Michigan, which managed to score the coldest winter in its weather history. Ironwood’s average temperature (including daily highs and lows) was a mere 5.1°F, which is 0.8°F colder than the previous record, set in 1978–79. Eau Claire, Wisconsin, tied its coldest-winter mark, and Duluth and International Falls, Minnesota, both had their second coldest winters on record. Many other cities from the northern Great Plains to the Great Lakes came in well below average.

Snowfall was also impressive, especially near the Great Lakes, where the natural snowmaking abilities of lake-effect circulations went into stunning overdrive. As of today, Detroit is just 9.8 inches away from its snowiest winter on record (93.6”, set in 1880–81).

Combine snowfall and cold, and you’ve got misery—a subjective state translated into numbers via Barbara Mayes Boustead, a forecaster at the National Weather Service in Omaha. Boustead and several colleagues have created the Accumulated Winter Season Severity Index, or AWSSI (pronounced “aw-see”), which was unveiled at last year’s annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society. Last month AWSSI went viral in national media and on the Web. The index draws on temperatures and snowfall through the winter to provide a cumulative measure of cold- and snow-induced suffering. As of last month, Detroit was on track for its worst AWSSI score of any winter on record.

There’s yet another facet to winter misery: the beauty of a fresh-fallen snow quickly fading as grime accumulates on it. However, across the eastern U.S., spells of unusual cold have been interspersed with occasional heavy rain and dramatic warm-ups, including the mildest night on record for meteorological winter in Baltimore. That’s helped keep snow cover from persisting across the South and mid-Atlantic for weeks on end, as it has in other areas. The warm spikes also truncated what could have otherwise been impressive strings of consecutive days below freezing, such as those observed in the 1970s and 1980s. (See the January 14 AtmosNews Perspective, “Cold but brief”).

Temperatures also had a surprisingly hard time hitting extremely low values in some areas. Even though Duluth had its second coldest winter on record, with 65 days dipping to at least 0°F, the city went from December through February without setting a single daily record low.

In fact, by some measures, the nation’s most impressive cold spell of the year occurred just this past weekend, after meteorological winter was over. On March 2, Billings, Montana, had its coldest March reading ever observed (–21°F). The high of 5°F in Kansas City, Missouri, was its lowest on record for any March day. Several other cities—from Pierre, South Dakota, to Longview, Texas, to Atlantic City, New Jersey—set all-time March lows. Even Duluth finally managed to score a daily record low, with a bitter –23°F.

It’s also important to note that this winter’s persistent cold from central Canada into the Midwest wasn’t global by any means. Europe and most of the Arctic were relatively balmy, with Germany having its fourth warmest winter in more than 100 years of records.

When Norway gets its largest wildfire in almost a century—and it’s a wildfire in January—you know that one strange winter is unfolding.