Groundbreaking data set gives unprecedented look at future weather

Computationally expensive project took years of effort to create

Dec 7, 2017 - by Laura Snider

Dec 7, 2017 - by Laura Snider

How will weather change in the future? It's been remarkably difficult to say, but researchers are now making important headway, thanks in part to a groundbreaking new data set at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

Scientists know that a warmer and wetter atmosphere will lead to major changes in our weather. But pinning down exactly how weather — such as thunderstorms, midwinter cold snaps, hurricanes, and mountain snowstorms — will evolve in the coming decades has proven a difficult challenge, constrained by the sophistication of models and the capacity of computers.

Now, a rich, new data set is giving scientists an unprecedented look at the future of weather. Nicknamed CONUS 1 by its creators, the data set is enormous. To generate it, the researchers ran the NCAR-based Weather Research and Forecasting model (WRF) at an extremely high resolution (4 kilometers, or about 2.5 miles) across the entire contiguous United States (sometimes known as "CONUS") for a total of 26 simulated years: half in the current climate and half in the future climate expected if society continues on its current trajectory.

The project took more than a year to run on the Yellowstone supercomputer at the NCAR-Wyoming Supercomputing Center. The result is a trove of data that allows scientists to explore in detail how today's weather would look in a warmer, wetter atmosphere.

CONUS 1, which was completed last year and made easily accessible through NCAR's Research Data Archive this fall, has already spawned nearly a dozen papers that explore everything from changes in rainfall intensity to changes in mountain snowpack.

"This was a monumental effort that required a team of researchers with a broad range of expertise — from climate experts and meteorologists to social scientists and data specialists — and years of work," said NCAR senior scientist Roy Rasmussen, who led the project. "This is the kind of work that's difficult to do in a typical university setting but that NCAR can take on and make available to other researchers."

Other principal project collaborators at NCAR are Changhai Liu and Kyoko Ikeda. A number of additional NCAR scientists lent expertise to the project, including Mike Barlage, Andrew Newman, Andreas Prein, Fei Chen, Martyn Clark, Jimy Dudhia, Trude Eidhammer, David Gochis, Ethan Gutmann, Gregory Thompson, and David Yates. Collaborators from the broader community include Liang Chen, Sopan Kurkute, and Yanping Li (University of Saskatchewan); and Aiguo Dai (SUNY Albany).

Climate models and weather models have historically operated on different scales, both in time and space. Climate scientists are interested in large-scale changes that unfold over decades, and the models they've developed help them nail down long-term trends such as increasing surface temperatures, rising sea levels, and shrinking sea ice.

Climate models are typically low resolution, with grid points often separated by 100 kilometers (about 60 miles). The advantage to such coarse resolution is that these models can be run globally for decades or centuries into the future with the available supercomputing resources. The downside is that they lack detail to capture features that influence local atmospheric events, such as land surface topography, which drives mountain weather, or the small-scale circulation of warm air rising and cold air sinking that sparks a summertime thunderstorm.

Weather models, on the other hand, have higher resolution, take into account atmospheric microphysics, such as cloud formation, and can simulate weather fairly realistically. It's not practical to run them for long periods of time or globally, however. Supercomputers are not yet up to the task.

As scientific understanding of climate change has deepened, the need has become more pressing to merge these disparate scales to gain better understanding of how global atmospheric warming will affect local weather patterns.

"The climate community and the weather community are really starting to come together," Rasmussen said. "At NCAR, we have both climate scientists and weather scientists, we have world-class models, and we have access to state-of-the-art supercomputing resources. This allowed us to create a data set that offers scientists a chance to start answering important questions about the influence of climate change on weather."

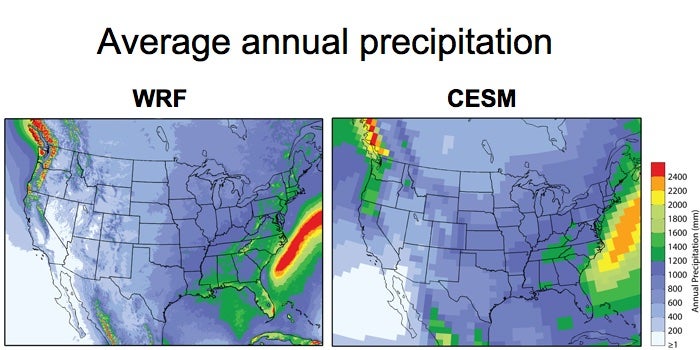

Weather models are typically run with a much higher resolution than climate models, allowing them to more accurately capture precipitation. This figure compares the average annual precipitation from a 13-year run of the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model (left) with the average annual precipitation from running the global Community Earth System Model (CESM) to simulate the climate between 1976 and 2005 (right). (©UCAR. This figure is courtesy Kyoko Ikeda. Ite is freely available for media & nonprofit use.)

To create the data set, the research team used WRF to simulate weather across the contiguous United States between 2000 and 2013. They initiated the model using a separate "reanalysis" data set constructed from observations. When compared with radar images of actual weather during that time period, the results were excellent.

"We weren't sure how good a job the model would do, but the climatology of real storms and the simulated storms was very similar," Rasmussen said.

With confidence that WRF could accurately simulate today's weather, the scientists ran the model for a second 13-year period, using the same reanalysis data but with a few changes. Notably, the researchers increased the temperature of the background climate conditions by about 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit), the end-of-the-century temperature increase predicted by averaging 19 leading climate models under a business-as-usual greenhouse gas emissions scenario (2080–2100). They also increased the water vapor in the atmosphere by the corresponding amount, since physics dictates that a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture.

The result is a data set that examines how weather events from the recent past — including named hurricanes and other distinctive weather events — would look in our expected future climate.

The data have already proven to be a rich resource for people interested in how individual types of weather will respond to climate change. Will the squall lines of intense thunderstorms that rake across the country's midsection get more intense, more frequent, and larger? (Yes, yes, and yes.) Will snowpack in the West get deeper, shallower, or disappear? (Depends on the location: The high-elevation Rockies are much less vulnerable to the warming climate than the coastal ranges.) Other scientists have already used the CONUS 1 data set to examine changes to rainfall-on-snow events, the speed of snowmelt, and more.

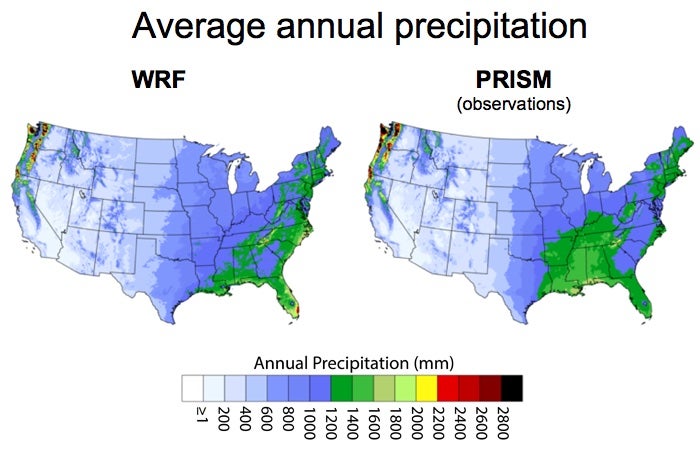

Running the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model at 4 kilometers resolution over the contiguous United States produced realistic simulations of precipitation. Above, average annual precipitation from WRF for the years 2000-2013 (left) compared to the PRISM dataset for the same period (right). PRISM is based on observations. (©UCAR. This figure is courtesy Kyoko Ikeda. It is freely available for media & nonprofit use.)

While the new data set offers a unique opportunity to delve into changes in weather, it also has limitations. Importantly, it does not reflect how the warming climate might shift large-scale weather patterns, like the typical track most storms take across the United States. Because the same reanalysis data set is used to kick off both the current and future climate simulations, the large-scale weather patterns remain the same in both scenarios.

To remedy this, the scientists are already working on a new simulation, nicknamed CONUS 2.

Instead of using the reanalysis data set — which was built from actual observations — to kick off the modeling run of the present-day climate, the scientists will use weather extracted from a simulation by the NCAR-based Community Earth System Model (CESM). For the future climate run, the scientists will again take the weather patterns from a CESM simulation — this time for the year 2100 — and feed the information into WRF.

The finished data set, which will cover two 20-year periods, will likely take another year of supercomputing time to complete, this time on the newer and more powerful Cheyenne system at the NCAR-Wyoming Supercomputing Center. When complete, CONUS 2 will help scientists understand how expected future storm track changes will affect local weather across the country.

Scientists are already eagerly awaiting the data from the new runs, which could start in early 2018. But even that data set will have limitations. One of the greatest may be that it will rely on a single run from CESM. Another NCAR-based project ran the model 40 times from 1920 to 2100 with only minor changes to the model's starting conditions, showing researchers how the natural chaos of the atmosphere can cause the climate to look quite different from simulation to simulation.

Still, a single run of CESM will let scientists make comparisons between CONUS 1 and CONUS 2, allowing them to pinpoint possible storm track changes in local weather. And CONUS 2 can also be compared to other efforts that downscale global simulations to study how regional areas will be affected by climate change, providing insight into the pros and cons of different research approaches.

"This is a new way to look at climate change that allows you to examine the phenomenology of weather and answer the question, 'What will today's weather look like in a future climate?'" Rasmussen said. "This is the kind of detailed, realistic information that water managers, city planners, farmers, and others can understand and helps them plan for the future."

High Resolution WRF Simulations of the Current and Future Climate of North America, DOI: 10.5065/D6V40SXP

Writer/contact:

Laura Snider, Senior Science Writer