How unusual is Moscow's heat?

Aug 9, 2010 - by Staff

Aug 9, 2010 - by Staff

Bob Henson | 9 August 2010 • In 1988, it was the spectre of Yellowstone National Park on fire. In 2003, it was the incongruous horror of thousands dying from heat in prosperous western Europe. This summer, the planet’s standout heat wave is the one now plaguing much of European Russia, including Moscow.

Weather Underground blogger Jeff Masters, someone who’s not prone to overstatement, has called the Russian heat wave “one of the most remarkable weather events of my lifetime.” Masters has done a superb job keeping tabs on the unfolding disaster, including this post of 6 August.

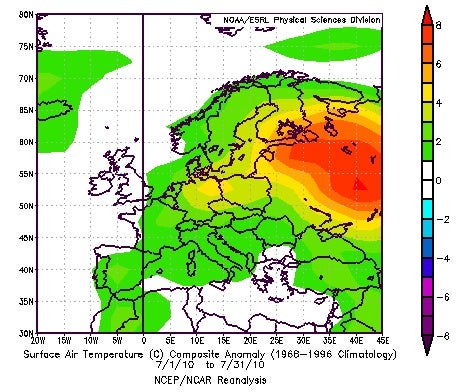

This graphic from NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory shows the departure from average, in degress Centigrade (right legend), for air temperatures in July 2010 across Europe.

The statistics from Moscow speak for themselves. Before last month, no reporting site in the city had ever reached the 100°F mark in 130 years of weather records. That all-time record was broken on 29 July, as the Moscow Observatory reached 100.8°F (38.2°C) and the Baltschug station hit 102.2°F (39.0°C). Every day since 13 July has reached at least 86°F (30°C), and Moscow's daily highs are predicted to top 90°F (32°C) through at least this week.

To put the Russian heat wave into a U.S. perspective, Moscow’s climate is somewhat like a less-variable version of what you'd expect in Minneapolis. Annual average temperatures are similar in both places. But when you examine winter and summer separately, important differences emerge.

Despite its reputation, Moscow tends to be less cold than the Twin Cities in winter, with typical lows in the mid-teens (Fahrenheit), whereas the average daily low in Minneapolis in January is a frigid 4°F (–15.6°C). What makes Moscow winters so harsh is their relentlessness: a “mild” spell usually means gloomy skies and temperatures hovering near freezing.

On the flip side, Moscow doesn’t normally get the blistering summer heat that can plague Minnesotans. During the brutal summer of 1936, Moorhead, Minnesota, hit 114°F (45.6°C), still the state’s all-time high. Summer afternoons in Minneapolis typically get into the low 80s, whereas Moscow’s average high is only in the low 70s.

Compare that to the readings seen in Moscow this summer. At Domodedovo Airport, the average daily high this past July was 90°F. The month as a whole ran 14°F (7.8°C) above average—a phenomenal departure for a 31-day period. Consider that Washington, D.C., managed to notch a tie for its warmest-ever month in July by running a mere 3.9°F (2.2°C) above average.

The human toll of Moscow’s intense heat is still being tallied. Smoke from nearby peat and forest fires is mingling with locally generated emissions to produce unhealthy air quality readings. On Friday, 6 August, the air was deemed as dangerous as smoking several packs of cigarettes each day. That leaves Muscovites with the unappealing choice of either breathing toxins outdoors or barricading themselves inside sweltering homes, most of which lack air conditioning. In Russia, as in Europe's catastrophic 2003 heat wave, cities that were built for cooler times struggle to deal with warmer weather.

Olga Wilhelmi on a 2009 visit to Moscow.

A researcher's roots

NCAR’s Olga Wilhelmi has a unique perspective on the Russian heat wave. She’s a native of Moscow as well as a geographer using GIS and other tools to help improve how cities respond to extreme heat. Wilhelmi says her family and friends in Russia are sending her a consistent message: “It’s a horrible summer.” Subways, in particular, have been pressure cookers, with temperatures as high as 90°F (32°C). “Imagine a subway train with hundreds of people during rush hour, traveling for 30 or 40 minutes,” says Wilhelmi. “This would be especially challenging for people with pre-existing health conditions, as well as the elderly and children.”

In the United States, many cities have instituted “cooling centers,” ramped up their warning systems, and launched other innovations in response to disasters such as Chicago's 1995 heat wave, which killed more than 700 people. According to Wilhelmi, Moscow’s meager experience with intense heat means that “most coping mechanisms are informal and very limited.” The city did open more than 120 rooms in air-conditioned buildings on 8 August as the heat continued.

One classic escape for Muscovites is the summer house, or dacha. Thousands of these are located in the countryside within 20 to 60 miles (30–100 kilometers) of Moscow’s city center. This year, says Wilhelmi, the dachas haven’t been as pleasant as usual, especially those that lie downwind from the peat and forest fires.

In the March issue of Environmental Research Letters (PDF; 764 kb), Wilhelmi and NCAR colleague Mary Hayden outline a new approach to analyzing cities’ vulnerability to extreme heat, using both qualitative and quantitative data. With this paradigm in mind, the two scientists have embarked on a multiyear study in Toronto and Houston called SIMMER. (See this NCAR Staff Notes article for more; a SIMMER website is also forthcoming.)

The deadly side of heat

More than 1,000 deaths have already been attributed to drownings in Russia during this summer’s heat. Some—but not all—of those drownings are alcohol-related, says Wilhelmi. Part of the problem, she adds, is that “people think they need to be hydrating with alcohol, which is the worst thing you can do.” But the heat itself may increase the risk of drowning. “One of the early symptoms of heat stress is confusion. If you’re already experiencing heat stress and you go in the water, you may make irrational choices.”

Mortality is often shockingly high in heat waves. Moscow recorded nearly 5,000 more deaths in July 2010 than in July 2009, and Jeff Masters has drawn on recent mortality reports to estimate that at least 15,000 Russians may have died as a result of this summer’s heat wave. Media coverage is beginning to highlight the terrible human toll the heat wave is taking. It will take months of work for experts to determine which of these deaths can ultimately be attributed to the heat, the simultaneous air pollution, or both. While it may take some time to gauge the full scope of this summer’s Russian tragedy, the ongoing suffering is all too apparent.