The October snow blitz: What made "Snowtober" so unusual?

Nov 16, 2011 - by Staff

Nov 16, 2011 - by Staff

It wasn't all that cold, but it certainly was wet.

November 8, 2011 • Autumn in New England brings to mind crisp air, dappled sunshine, and explosions of scarlet foliage—not tree-breaking snowfall. Yet nature ignored the calendar this year and delivered the biggest October snowstorm ever recorded for many areas from the Mason-Dixon line to Maine. On mainstream and social media, it’s been dubbed “Snowtober.”

A huge swath of snow from West Virginia to Maine is evident in this image captured on 30 October by MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) aboard NASA’s Terra satellite. (Image courtesy NASA Earth Observatory.)

In Central Park, the 2.9” of snow on the 29th was the largest October accumulation ever witnessed and one of only four measurable snows for October since records there began in 1869. Even Washington, D.C., got a dusting (0.6” at Dulles International Airport and a trace at Reagan National). Huge amounts fell from northwest New Jersey (West Milford recorded 19.0”) to southern New Hampshire (23.0” in Concord).

Not only did this storm deliver hardship and inconvenience on a grand scale—more than three million utility customers lost service, on par with the toll from a major hurricane—but it also brought an acute sense of dislocation. Although the storm itself was well forecast, its aseasonality caught people’s psyches off guard, a bit like a dinner-party guest who calls at 11:45 a.m. and says he’s dropping by at noon.

Even the autumn routines of the National Weather Service took a hit. The agency’s long-scheduled winter weather awareness week kicked off across New England on Halloween, 31 October, by which point awareness was already sky high. The NWS’s Boston office acknowledged the mismatch: “Nevertheless, winter has technically not arrived yet, and we would like to reiterate winter weather safety information.”

Snowflakes in October aren’t completely foreign to Northeasterners. During 3–4 October 1987, New York’s Catskill Mountains were plastered with as much as 20” of wet snow. And a narrow band of snow on 9–10 October 1979 gave Washington, Philadelphia, and New York their earliest-ever accumulations. But because storms like this occur when temperatures are barely cold enough to snow, they typically affect a small area. Not so in 2011.

“This behaved more like a traditional midwinter storm,” says NOAA’s Paul Kocin. He and NOAA/NCEP director Louis Uccellini wrote the two-volume book Northeast Snowstorms, the definitive treatment of the topic. (A third volume focusing on 21st-century storms can be expected in a few years, says Kocin: “I’ve already got a folder started on this one.”)

In classic nor’easter fashion, the storm featured an initial push of energy and cold air that brought several inches of snow to parts of New England on Thursday night, 27 October. This was followed on Friday night and Saturday by the rapid spin-up of a surface low that tracked about 100 miles offshore. The one-two punch ensured that enough cold air would be entrenched to keep the surface low from pushing warm marine air well inland.

New York’s Central Park was ravaged by the “Snowtober” storm. More than 1,000 trees may be lost across nearly half of the park’s 843 acres. Much of the damage was in the heavily visited southern portion. (Image courtesy Central Park Conservancy.)

Not that the inland temperatures were all that cold. It never dipped below freezing in Central Park until the snow was gone. And although a number of snowfall records were shattered across New England, not a single daily record low minimum was broken.

In a less intense storm, the snow might have melted nearly as fast as it fell. But this was a notably powerful system, fueled by a strong jet stream, unusually warm waters southeast of New England, and a channel of low-level moisture extending south toward the remnants of Hurricane Rina. The dynamics of the storm led to snowfall rates as high as 2 inches per hour, more than enough to overpower any melting from below. And the snow itself helped chill the low-level air.

To top things off, many of the trees across the heaviest belt of snow were still laden with foliage, thanks to a largely damp and mild autumn. That pushed the storm’s capacity to bring down limbs and power lines far beyond what it would have been if the leaves had fallen sooner. Even the small accumulation in Central Park caused damage that may require more than 1,000 trees to be removed—more than any weather event in years, according to the Central Park Conservancy.

“In the history of early-season snowstorms, there are always freakish cases, but you have to hunt to find something of this magnitude,” says Kocin. Perhaps the only rival comes from the tail end of the Little Ice Age. In the Snow Hurricane of 1804, a tropical cyclone swept up the coast and plowed into a large mass of cold air over New England. Weather records of the time are sketchy, but the storm clearly made its mark with substantial snow on 10–11 October, as suggested by an 1891 account. Up to 30 inches fell in the Berkshires of Massachusetts.

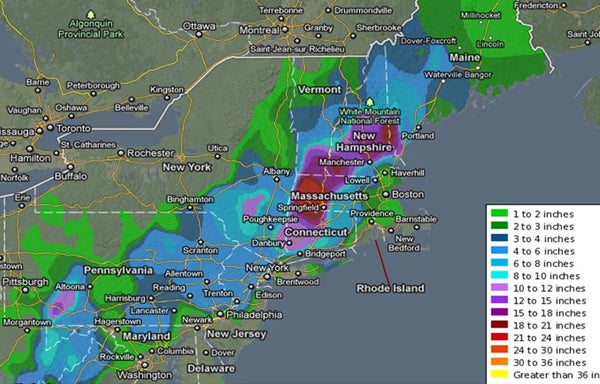

More than a foot of wet snow during the late-October storm brought down many thousands of trees and power lines. The heaviest snow totals were across western Massachusetts. (Image courtesy National Weather Service; NOAA data atop Google base map.)

In a year already checkered with noteworthy atmospheric and geophysical extremes, from tornadoes to tsunamis, the October snow blitz led to a fresh round of questioning: What’s with this wacky weather? Early snows in New England aren’t something that climate-change analysts have been looking for, and none of them are projecting that snowplows will join pumpkins as icons of Halloween in the Northeast.

What has drawn the attention of climate watchers is the string of intense precipitation events of late, several of them focused in the Northeast. Along with this year’s early snow, these include record-breaking midwinter snows in early 2010 and early 2011 and the deluge from Hurricane Irene last August. Central Park has notched its third wettest year on record, with 65.76” of liquid as of 3 November.

Many locations around the world are reporting an increase in the amount of rain and snow falling in heavy bursts, notes NCAR’s Kevin Trenberth. For every 1°C rise in air temperature (1.8°F), the atmosphere's potential capacity for water vapor increases by about 7%, Trenberth points out. A moistening atmosphere can team with higher temperatures to help boost the rain- and snow-making capacity of hurricanes and winter storms. The increased evaporation also pulls moisture from dry soil, paradoxically helping to strengthen droughts as well.

As Trenberth points out in a recent overview for the journal Climatic Research, computer models may be underplaying the intensification of precipitation. “Finding out what is happening to precipitation and storms is vital,” he says. Ample moisture was clearly one of the many ingredients that came together in a devastating way over the Northeast. The result: a thick coat of icing on this year’s layer cake of weird weather.

“If this year’s storm had occurred at the end of November, we’d be calling it an unusual early-season snowstorm,” says Kocin. “This is about as anomalous as it gets.”