New computer simulations reveal the Earth system in unprecedented detail

Freely available dataset offers unique research opportunities

Feb 4, 2026 - by David Hosansky

Feb 4, 2026 - by David Hosansky

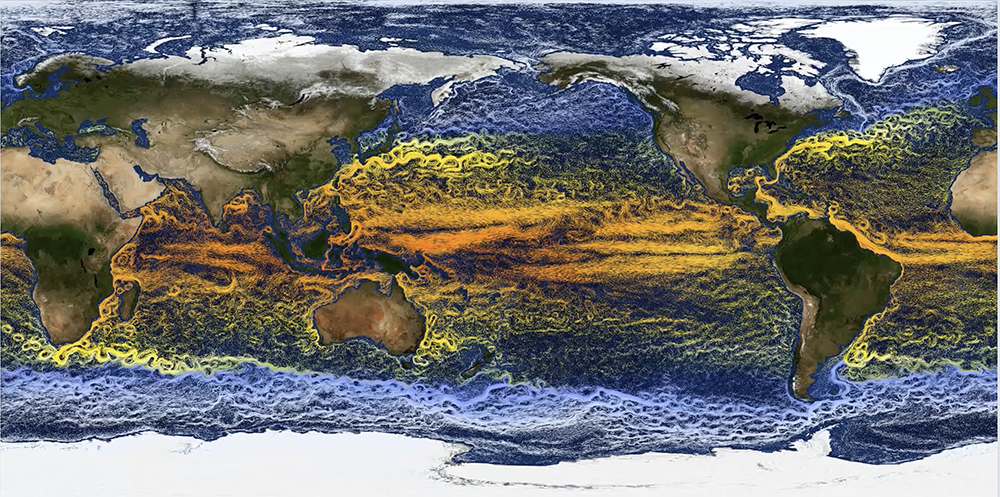

The high-resolution simulations in the MESACLIP dataset include such features as snow cover on land and sea surface temperatures in the oceans.

Leveraging the power of two of the nation’s leading supercomputers, a team of scientists at Texas A&M University and the U.S. National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR) has created an unprecedented set of high-resolution Earth system simulations. The dataset is freely available to the scientific community, offering a remarkable opportunity to gain new insights into climate variability and how future changes may affect specific regions.

The project, called MESACLIP, is unique with multiple high-resolution runs, or ensembles, that sample the inherent, natural fluctuations of the Earth’s climate system. The massive dataset, weighing in at over six petabytes, provides scientists with an extraordinary trove of simulations spanning more than 4,500 years of past, present, and future climate on which to conduct experiments.

MESACLIP is already demonstrating its value. A recent paper in Nature Geoscience showed how extreme precipitation events may increase due to shifts in winds and the accumulation of moist air in the atmosphere. Researchers are also mining the dataset to advance understanding of large-scale ocean currents that affect regional climate, atmospheric rivers that drive powerful storms, tropical cyclones and sea level changes that can impact low-lying coastlines, ocean upwelling that affects fisheries, and more.

“MESACLIP is a major accomplishment, and it creates exciting research opportunities for many people across the scientific community,” said NSF NCAR scientist Gokhan Danabasoglu, who is the NSF NCAR lead of the project. “It significantly enhances our view of the Earth system.”

He added that the dataset will be especially valuable as scientists seek to improve predictions of weather patterns and storm tracks months to years in advance. Such seasonal to decadal forecasts are vital for agriculture, energy, and other economic sectors, potentially saving businesses billions of dollars and helping communities prepare for severe droughts, prolonged heat waves, and other weather and climate impacts.

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation.

When scientists model Earth’s climate, they typically rely on lower-resolution simulations. This is because the climate system is so complex — encompassing the atmosphere’s interactions with the world’s oceans, sea ice, and land surface — that zooming in to explicitly resolve features smaller than about 100 kilometers typically requires prohibitively expensive computational resources, especially for climate scale simulations that span decades to centuries.

Such simulations provide invaluable insights into general trends of Earth’s changing climate. But they cannot explicitly capture smaller features such as individual cities, mountain ridges, and hurricanes, leaving scientists to estimate some of the finer-scale impacts of warming temperatures.

In contrast, weather models — which simplify the Earth system and predict the weather only for a week or two — often have a global resolution of about 10 kilometers. They’ve even been run experimentally at NSF NCAR at a global resolution of 3 kilometers.

To explore how Earth’s climate would look at a finer-scale resolution, a team of scientists — including Danabasoglu and Texas A&M professor Ping Chang — turned to one of the world’s leading Earth system models, the NSF NCAR-based Community Earth System Model (CESM). Over three years, they ran simulations at a resolution of 25 kilometers for the atmosphere and 3-10 kilometers for the ocean.

Such high resolution, unprecedented for large ensembles of Earth system modeling runs, was made possible because of recent advances in supercomputing speed. The modeling was conducted on two of the nation’s leading supercomputers for scientific research: the Derecho supercomputer at the NSF NCAR-Wyoming Supercomputing Center in Cheyenne and the Frontera supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center at the University of Texas at Austin. So extensive were the model runs on Derecho that, when completed (some of the modeling is still ongoing), they will have used about 25% of that supercomputer’s capacity for a year.

The MESACLIP modeling recreates past climate from 1850, and it extends out to 2100 based on various scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions. Some of the simulations were run as many as 10 times with slightly different initial conditions to reveal natural variations.

“One of our goals with MESACLIP is to provide a community resource that supports varied scientific investigations,” Chang said. “By releasing this dataset publicly, we hope to empower researchers to tackle a wide range of climate questions that require high spatial resolution and long simulations.”

Danabasoglu and his colleagues say the early results are already providing new insights into Earth’s changing climate system, helping scientists address key questions with profound societal implications.

“We are starting to find evidence that moving to this finer resolution is going to change much of our understanding of the Earth system,” said NSF NCAR scientist Frederic Castruccio, one of the project leaders.

For example, the high-resolution simulations indicate that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation — a major current that pumps warm tropical waters to upper latitudes — is likely to continue to shield Europe from frigid temperatures. Some lower-resolution models had suggested the current could soon collapse.

The MESACLIP modeling has also successfully reproduced a puzzling trend of cooling temperatures that has occurred in the Southern Ocean and eastern Pacific Ocean over the past few decades. The trend, which lower-resolution models failed to capture, may be linked to the ozone hole above Antarctica that has cooled the stratosphere and fueled powerful winds that encircle the Southern Ocean.

Another finding from the recent paper in Nature Geoscience, which was co-authored by Chang, Danabasoglu, and their colleagues at Texas A&M and NSF NCAR, showed that daily extreme precipitation could increase by 41% over land this century, with potentially even higher increases in the southeastern United States. The reason has to do in part with small-scale wind patterns, including stronger updrafts that fuel powerful storms — which were not captured in lower-resolution models.

Even while touting the advantages of the high-resolution simulations, Danabasoglu and Castruccio warn that the simulations are far from perfect. For example, they often fail to reproduce aspects of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, which is one of the planet’s most influential climate features.

Partly for that reason, the MESACLIP team is planning a new set of simulations that will provide even more insights into the Earth system. This will involve using CESM3, which will be the most powerful version of NSF NCAR’s flagship model when it is released later this year. At the same time, scientists hope other scientific organizations will create similar high-resolution simulations with their own climate models, providing an opportunity to compare results.

“We are looking forward to other groups creating high-resolution simulations,” Danabasoglu said. “These early results are all based on our model. Once we have multiple models working on these important problems, it will give us even more confidence for future projections.”