Ice vs. storm: 2012’s Great Arctic Cyclone

Two rarities lead to a colossal matchup

Aug 17, 2012 - by Staff

Aug 17, 2012 - by Staff

Bob Henson • August 16, 2012 | As Shakespeare noted about true love, the course of Arctic sea ice never does run smooth. Even though weather conditions in June and July weren’t especially favorable for melting, the ice vanished at a striking pace. Then came a midsummer tempest—and now 2012 threatens to break 2007’s records for the lowest extent of Arctic sea ice ever observed.

This mosaic of NASA/MODIS satellite images from August 5 shows a massive low-pressure center spinning across the central Arctic Ocean on August 5, 2012. Canada and Alaska are located to the left, with Europe and Russia to the right. (Image courtesy NASA Earth Observatory.)

I knew something was afoot when I turned to the indispensible Arctic Sea Ice Blog a few days ago and saw the headline “Cyclone warning!” Computer models were indicating that a vast, powerful area of low pressure would develop over the central Arctic Ocean and stay in place for days. The storm didn’t last quite as long as forecast, but it was indeed a humdinger, one that could stimulate research for years to come.

Just how unusual was this cyclone? It’s surprisingly hard to get a precise answer, since Arctic Ocean weather is so difficult to observe. For decades, surface pressure was measured only on a few Arctic islands, at a few land-based stations ringing the ocean, and with an array of floating buoys. Satellite cloud photos also helped estimate surface pressures, but routine, high-quality satellite monitoring did not begin until 1979.

Nevertheless, it’s clear this storm was “truly remarkable,” says Ian Simmonds (University of Melbourne). He and Mark Drinkwater (European Space Agency) produced a paper in 2007 for the World Meteorological Organization entitled “A ferocious and extreme Arctic storm in a time of decreasing sea ice” (PDF). Their study analyzed a low that spun across the Arctic in August 2006, with a central surface pressure that dipped to 984 hectopascals—on par with a major U.S. winter storm.

This year’s Great Arctic Cyclone leaves that “ferocious” storm in the dust, with a central pressure that bottomed out at 963 hPa. No other summer storms—and only a tiny number of winter storms—have been that intense across the Arctic since 1979, according to Simmonds, who led a study of Arctic cyclones published in 2008 in the Journal of Climate.

Early-spring sunlight hits ice in the Chukchi Sea near Barrow, Alaska, in March 2009. This image was taken during the OASIS (Ocean–Atmosphere–Sea Ice–Snowpack) field project, part of the International Polar Year. (©UCAR. Photo by Carlye Calvin.)

As Simmonds points out, central pressure is just one way to assess a storm’s strength. Stu Ostro (The Weather Channel) dug into the data to see whether any other Arctic storms had been so intense at middle altitudes: 500 hPa, several miles above the surface. Looking at the interval from July 15 to August 15 for the period 1948–2012, Ostro found only one system anywhere in the Northern Hemisphere with a 500-hPa intensity comparable to the one observed earlier this month. (In this case, intensity is measured by the height of the 500-hPa surface: the lower it is, the stronger the system.)

It was that upper-level storm moving north from Siberia last week that triggered the surface cyclone, says Steven Cavallo. Now at the University of Oklahoma, Cavallo analyzed tropopause polar cyclones with graduate advisor Gregory Hakim during his studies at the University of Washington. Cavallo thinks the strength of the Great Arctic Cyclone is likely a product of the strong contrast between unusually warm waters in the East Siberian and Laptev seas and the edge of the remaining sea ice, around 75–80°N. Normally, he says, “we see more extreme cyclones in the autumn or spring, because there’s a greater temperature difference between the colder atmosphere and warm ocean waters.”

If the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 was a truly unusual midsummer event, what makes it virtually unprecedented was the state of the ice beneath it. The storm’s high winds and waves pummeled a mammoth zone of ice that was already thin and fragmented.

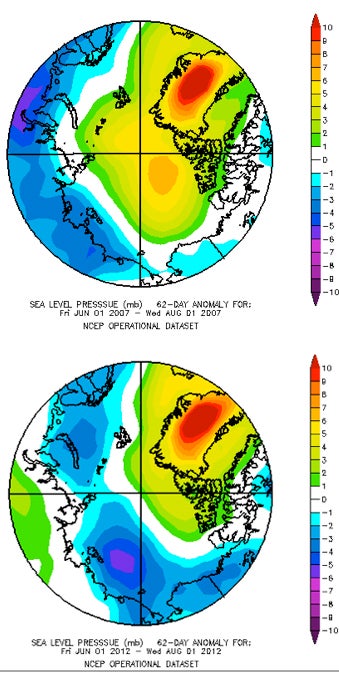

These maps show how much the average surface pressures for June–July 2007 (top) and 2012 (bottom) departed from average across the Arctic Ocean. In 2007, when sea ice extent dropped to record-low values, high pressure dominated the Arctic basin, centered in the Beaufort Sea and Greenland. This year, the zone of high pressure has been less extensive, but the amount of melt may exceed the 2007 record. (Images for 2007 and 2012 courtesy NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory.)

NCAR’s Jennifer Kay has studied the critical role of summer weather in shaping how much Arctic sea ice will melt in a given year. The most ice-destructive pattern, dubbed the Arctic Dipole, features relatively high pressure extending from the Beaufort Sea to Greenland. This helps keep skies clear, allowing for round-the-clock sunshine. It also tends to push ice from the western Arctic toward the Fram Strait and into the meltyard of the North Atlantic.

“This year’s pattern is not the canonical one for ice loss,” notes Kay. As evident in the maps at right, there’s been a tendency toward lower-than-usual pressure north of Alaska, which runs counter to the classic Arctic Dipole. However, consistent with the dipole, Greenland has seen higher-than-usual pressure (as well as headline-inducing melt extent atop its ice sheet and total melting already at record values). And both ocean and air temperatures across much of the Arctic have been consistently warm. For example, at Alert, Canada—the northernmost settlement on Earth, where average midsummer highs are around 42°F (6°C)—temperatures soared above 50°F (10°C) on at least 14 days in July and August.

Exactly how the Great Arctic Cyclone influenced this year’s already-depleted sea ice is still an open question. “There are many reasons to believe that a big storm could have a large effect on the sea ice,” observes James Screen (University of Melbourne). Such a storm might pull warmer air into the high Arctic; its waves and winds could break up large chunks of thin ice into smaller, easier-to-melt pieces; and the resulting ocean currents could push ice together, reducing the total extent of sea ice (though not fostering melt per se).

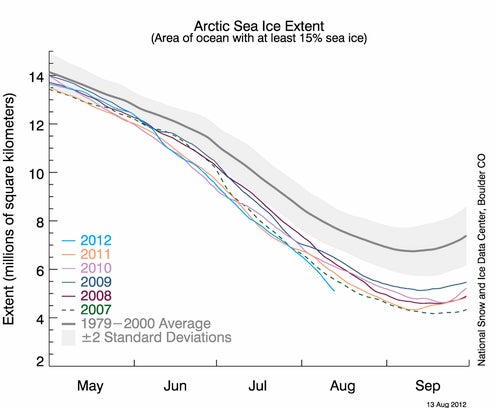

As the cyclone unfolded, many ice watchers on the Arctic Sea Ice Blog viewed it as a potential game changer for this summer’s ice loss. In fact, major drops did occur in most ice indexes over the first two weeks of August, including those calculated by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (see graphic at bottom). Near the cyclone’s track, a huge chunk of ice roughly the size of Norway split off from the central Arctic. Now marooned north of Siberia, that vast iceberg could melt completely by early autumn.

But in the Arctic, as elsewhere, correlation doesn’t necessarily imply causation, as experts hasten to point out. “Short-term accelerations of sea ice melt aren’t unprecedented, and they can occur in response to many complex factors,” says Screen.

In its August 14 update, the National Snow and Ice Data Center stopped short of attributing the rapid early-August ice loss in the East Siberian Sea to the cyclone, noting that “it may be simply a coincidence of timing, given that the low concentration ice in the region was already poised to rapidly melt out.”

We’re still far from September, when the Arctic’s sea ice normally hits its annual minimum. But signals are increasingly pointing toward melt that’s unprecedented in Arctic records. In a set of outlooks updated each month by a panel of experts, 12 of the 23 forecasts for sea ice extent now call for 2012 to match or exceed 2007’s record low value.

Aside from extent, there are several other ways to gauge ice loss. Most of them are on pace to approach or set records over the next few weeks, and their nuances are worth more discussion down the line. For now, suffice it to say that one index—sea ice area, as calculated by Cryosphere Today—has just dipped below 3 million square kilometers. That’s already close to the lowest value observed at any point in any year in the satellite era, with further melting yet to come.

The extent of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean broke ahead of the record-setting pace of 2007 during the first two weeks of August 2012. (Illustration courtesy National Snow and Ice Data Center.)