¡Hola, La Nada!

What happens when El Niño and La Niña take a break?

Nov 9, 2012 - by Staff

Nov 9, 2012 - by Staff

Bob Henson • November 9, 2012 | It’s official: NOAA has cancelled the El Niño Watch that was in effect since June (see PDF). But if you think this guarantees a placid U.S. winter, you might find yourself surprised.

El Niño and its counterpart, La Niña—together referred to as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO)—shape seasonal climate across North America and elsewhere. They respectively warm and cool the surface waters of the eastern tropical Pacific, typically for a year or two at a time, which in turn triggers a chain of atmospheric responses around much of the globe. ENSO’s influence tends to grow during northern autumn and peak from around year’s end into northern winter. Fishermen observing the warming of Pacific waters at that time of year gave "El Nino" (which means "the Christ child") its name.

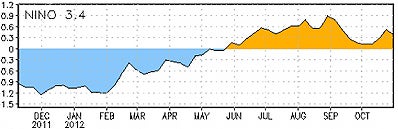

Sea-surface temperatures in the Niño3.4 region of the tropical Pacific haven’t been able to stay above the El Niño threshold of 0.5°C in recent months. (Image from Weekly ENSO Update, courtesy NOAA Climate Prediction Center.)

In both 2010–11 and 2011–12, La Niña ruled the roost. The cooler ocean water tends to favor colder-than-average weather toward the northern and western United States and relative warmth in the Southeast, with an active storm track in between. But neither La Niña nor El Niño guarantee any particular outcome: they simply shift the odds. While the winter of 2010–11 was notably cold in the Midwest, 2011–12 brought record warmth.

NOAA now projects that the most likely outcome this winter is neither El Niño nor La Niña but a neutral state, sometimes referred to informally as La Nada. “Neutral” means that sea-surface temperatures across the key Niño3.4 region (see graph above) are within 0.5°C of average. More formally, an El Niño or La Niña is declared when a three-month running average of the SST anomaly stays above or below the 0.5°C threshold for at least five months. (Here are the three-month running averages since 1950.)

The tropical Pacific is actually within the neutral range about half of the time, but mostly that’s when the system is moving into or out of El Niño or La Niña, typically from northern spring through fall. It’s more unusual for the average Niño3.4 temperatures to be in the neutral range during northern winter (December to February). This occurred during four of the five winters from 1989–90 to 1993–94, and again in 1996–97, but it’s happened only twice in the last 15 years: 2001–02 and 2003–04.

Most snowfalls in Seattle are light, but a multiday storm in mid-December 2008 brought the city its heaviest snowfall in years. Seattle's rare major snowstorms are most likely to occur when ENSO is in a neutral phase. (Wikimedia Commons photo by Alex O’Neil.)

So what can we expect in an ENSO-neutral winter? The atmospheric circus doesn’t stop just because El Niño and La Niña are offstage. Without those two elephants in the room, other forms of natural variability, as well as long-term trends, can become more obvious.

“The main effect of a weaker ENSO signal is that the probabilities in the climate forecast tend to return more toward climatological averages,” says Tony Barnston, chief forecaster at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society. “But trends do remain in play with or without ENSO.” For example, the ongoing tendency toward warmer U.S. winters (which has persisted despite the occasional Snowmaggedon event) should make a milder-than-usual winter somewhat more likely than a colder-than-usual one—especially in the Southwest, where a warming trend is most pronounced.

Storms may also play out in a less predictable way than usual, since the tendency of El Niño and La Niña to direct storminess toward a particular region isn’t expected this winter. “Weather patterns are not locked in as strongly, so they are more likely to be varying all over the place,” says NCAR’s Kevin Trenberth.

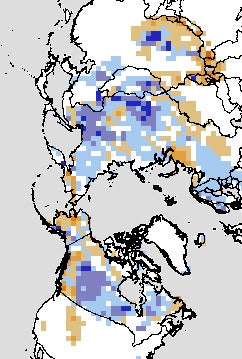

Snow cover in October 2012 was more extensive than usual across large parts of northern Europe and Russia, according to this satellite-based analysis. Blue regions are where snow was more prevalent than usual; tan indicates less snow cover than usual. (Image courtesy Rutgers University Global Snow Lab.)

In Seattle, ENSO-neutral winters tend to generate average amounts of snowfall, but they’re also the most likely ones to produce the occasional major winter storm, according to a recent blog post by Cliff Mass (University of Washington.) And a study of California floods carried out some years back found that the worst events can happen just as easily during neutral years as during El Niño or La Niña, even though the latter play big roles in the state’s total seasonal precipitation.

The strongest influence on this winter might be one that’s hard to predict: the Arctic Oscillation (closely related to the North Atlantic Oscillation). When the AO is positive, there’s typically a strong west-to-east jet stream across the oceans and into the continents, typically bringing mild marine air with it. A negative AO means a weaker west-to-east jet stream, allowing allows giant mounds of high pressure to spill southward from the poles toward midlatitudes.

When it's in a negative phase, the AO can bring frigid readings and heavy snow to the eastern United States. As the AO dipped to record lows in 2009–10 and 2010–11, brutal winter storms walloped the mid-Atlantic and parts of Europe. But the AO is far more mercurial than ENSO: its modes often last just several weeks, and they can change sign in a matter of days.

It’s impossible to be certain whether the AO will favor its positive or negative mode this winter, but there may be some predictive value in mid-autumn snowfall patterns across Eurasia. In a multiyear NSF-supported project, scientists at Atmospheric and Environmental Research and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have employed this correlation in AER’s U.S. winter outlooks. The company hasn’t yet publicized its 2012–13 outlook, but October left an unusually large swath of early snowfall across northern Europe and Siberia. Presumably, this would favor at least some periods of negative AO and an enhanced risk of snowstorms across the northeast United States. (Already, New York City, Newark, and Bridgeport, Connecticut have notched their heaviest snows on record for so early in the season, thanks to this week's nor'easter.)

A more subtle factor is the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, an index of sea-surface temperatures across the North Pacific. The PDO is a bit like a memory bank for ENSO: as El Niño and La Niña events come and go, their effects accumulate in the North Pacific, sometimes influencing water temperatures as deep as 1,000 feet (300 meters). “The North Pacific acts as what I like to call a ‘climate integrator,’ " says Matt Newman (University of Colorado), a longtime PDO researcher.

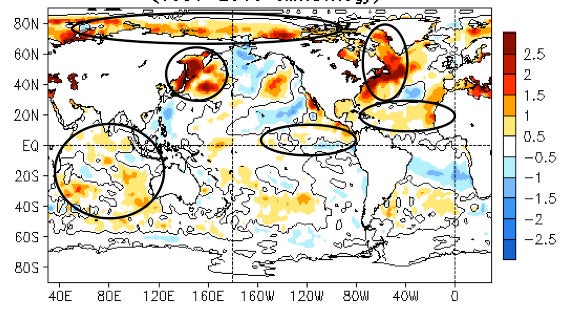

During October 2012, waters off the midlatitude coast of Asia and North America were unusually warm—more than 2°C (3.6°F) above average in some cases. (Image from Monthly Ocean Briefing, courtesy NOAA Climate Prediction Center.)

Over the last decade, as La Niña has dominated over El Niño events, the PDO has trended negative. However, there’s little sign that the PDO itself is useful as an independent predictor of winter weather over the United States, as confirmed in a new study led by NOAA’s Arun Kumar.

If there’s anything striking about current ocean conditions around the globe, it’s the impressive blobs of warmer-than-usual water located off the midlatitude coasts of Asia and North America, close to where the Kuroshio and Gulf Stream currents branch out into the North Pacific and North Atlantic, respectively. The unusual warmth off the U.S. mid-Atlantic helped fuel Superstorm Sandy, while warmth in the northwest Pacific—overlapping with a negative PDO, but centered much farther west—might help shape conditions downstream, according to several studies over the last few years.

What might that mean for U.S. weather? “That’s a good question. I don’t think there’s a good answer yet,” says Newman. He’s now using high-resolution modeling to study the problem through an NSF-funded collaboration with NCAR, NOAA, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

One thing worth keeping in mind is that El Niño could yet have an influence this winter, if only in muted form. “The 0.5°C threshold is not an on-off switch,” notes Michelle L’Heureux (NOAA Climate Prediction Center). “You can sometimes still get limited effects on U.S. winter even if it’s only modestly warm. But it can be tough to isolate a clear signal of this.”

NOAA’s seasonal outlooks, updated around the middle of each month, provide a useful way to track how experts view the factors at work. Without a strong El Niño or La Niña on the scene this winter, it’ll be interesting to see how other weather-shaping elements come into play, both in the seasonal outlooks and in the winter itself.